SEPTEMBER 2 1945

Above: 680 Navy aircraft from the carriers of the Third Fleet fly over USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on September 2, 1945. The flyover took two hours and one participant recalled “It was a miracle there wasn’t one mid-air collision and everyone had gas to get back and land on their carrier.”

Above and below: Crewmen and anyone else who could find a way to get to Missouri await the arrival of the Japanese surrender delegation.

Today, September 2, 2022, is the 77th anniversary of the Japanese surrender, ending World War II, six years and one day after it began September 1, 1939 with the German attack on Poland.

These are my two favorite stories of the end of the war. Each was personally told to me by the man who experienced it.

On September 1, 1945, Second Lieutenant Lamar Gillet, an Army pilot who had flown in the defense of the Philippines after Pearl Harbor and managed to become the only P-35 pilot to shoot down a Zero during the desperate fighting before he became one of the “Battling Bastards of Bataan” and then a survivor of the Bataan Death March, later surviving nearly three years as a slave laborer in Japan, was awakened in his POW camp on a hill overlooking the Sea of Japan in western Honshu, by the roar of engines. B-29s had flown over the camp many times before, but never this low.

The men poured out of their barracks and hobbled or ran into the open field. Gillet, who now weighed 95 pounds, down from the 145 he had weighed when he first arrived at Clark Field in the summer of 1941 to join the 17th Pursuit Group, looked up as the first bomber opened its bomb bay doors. Objects fell from the bomber, quickly slowed in their fall by parachutes. The other bombers followed, and the sky was now full of parachutes.

A B-29 in flight

“They got closer, and we could see they were crates. All of a sudden we were running away to dodge them as they fell into the field where we were. They came down hard, and several of them burst open on impact.” Most of the crates were full of C-rations, while others were full of clothing and boots and other items.

“I ran to one and grabbed a box of the C-rations, then ran to another and found a pair of GI boots that looked like they might fit.” Gillet retreated from the scramble and pulled on his boots. “They were a bit big for me, but I didn’t care. I had boots!” He then tore open the box of C-rations. “One of the cans was labeled ‘peaches.’ I hadn’t seen a peach since the day before the Japanese had bombed Clark Field the first day of the war.” There were no eating utensils in the box, but there was a can opener. “I opened that can, and I started scooping out those peaches and eating them with my fingers. I looked up at the bombers as they flew away, standing there in my new boots and dripping peach juice down my chin, and I was in hog heaven.”

On the morning of September 2, the Allied fleet was at anchor in Tokyo Bay, ready for the arrival of the Japanese representatives and the formal surrender ceremony.

A P-38 over Southern California

Ten thousand feet overhead, 23-year old Captain Paul Williams, a P-38 pilot in the 7th Fighter Squadron of the famed 49th Fighter Group, orbited over the fleet on combat air patrol. The “Forty Niners” were the first American fighter group to arrive in Australia after Pearl Harbor, and had participated in every battle from the defense of Darwin in the spring and summer of 1942, through all the fighting in New Guinea and the Philippines, up to Okinawa and the final missions over Japan.

Captain Williams, however, had arrived “late to the party” as he described it. “I finally got a combat assignment in March 1945, after two years as an instructor at Luke Field, but by the time I got to Clark Field and joined the group, there wasn’t any fighting left in the Philippines.” The group moved up to Okinawa in early June, and Williams flew missions to the coast of China, and over Kyushu, to which the enemy did not respond. “I really, really wanted to have one unforgettable experience in World War II, but it appeared I was destined to be disappointed.”

Following the surrender, the Forty-Niners were the first USAAF fighter group to arrive in Japan a week earlier, taking up residence at the old Imperial Navy air base at Atsugi.

As the sun rose over the western Pacific and the ships became silhouettes on the water below, Williams recognized the battleship “Missouri,” which was to be the site of the coming surrender ceremony. “I decided I wanted to have at least a minute of excitement to put in my memories of this war, so I radioed the ship and asked for permission to make a low pass over her. The radio shack said OK, so down I went.”

The Allied fleet in Tokyo Bay for the surrender.

On the way down to sea level, Williams decided he would make that minute not only memorable but spectacular. Rather than a low pass down the side of the ship, he decided to fly over it, between the massive stacks. “I figured I couldn’t do it wings level, so when I was about a thousand feet out, I rolled left wing high and went between the stacks wings-vertical at maximum speed, maybe 300 knots. There was a moment when I thought I’d misjudged things and was going to become a dead bug on the after stack, but I went right through between them!”

Williams rolled his wings horizontal as he pulled back on the yoke and the big fighter soared into the dawn sky. It was time to return to Atsugi.

“I had the first inkling I was in some big trouble when two MP jeeps pulled out and followed me to where I stopped and shut down. I climbed out and this big MP lieutenant came up and put me under arrest.”

Williams was taken to the group headquarters and shown into a room. He snapped to a very rigid attention when he recognized the man behind the desk: Major General Paul D. “Squeeze” Wurtsmith, the 33-year old general commanding Fifth Air Force Fighter Command. Wurtsmith had led the Forty-Niners to Australia in 1942, and was legendary throughout the Southwest Pacific as no one to cross.

“I had visions of spending Christmas in the stockade when he started an epic chewing-out about what the hell did I think I was doing, buzzing the flagship of the fleet. Didn’t I know there were rules against that? I suddenly remembered I’d called the ship and gotten permission. I blurted that out, and the general stopped. Then he picked up the phone and it didn’t take any time at all for him to be connected to the ship, and then to the radio shack. I was sure hoping those sailors might have written something down about my call. I was sucking attention like a first week ground school cadet while I listened to his side of the conversation. It seemed to take forever, but finally he hung up.”

Williams was given the order to stand at ease. Wurtsmith glared at him for what seemed an hour before he finally said, “You’re a lucky man. You get to walk out of here a Captain and not a Private. They did clear you to make that pass. Dismissed.”

Williams turned to leave, but Wurtsmith stopped him. “They said to tell you that was one helluva buzz job, Captain.”

Williams remembered he had difficulty getting through the door to leave the office, and it felt like he floated down the hallway. “I got to go home a Captain and not a Private, and I did have one unforgettable experience in World War II.”

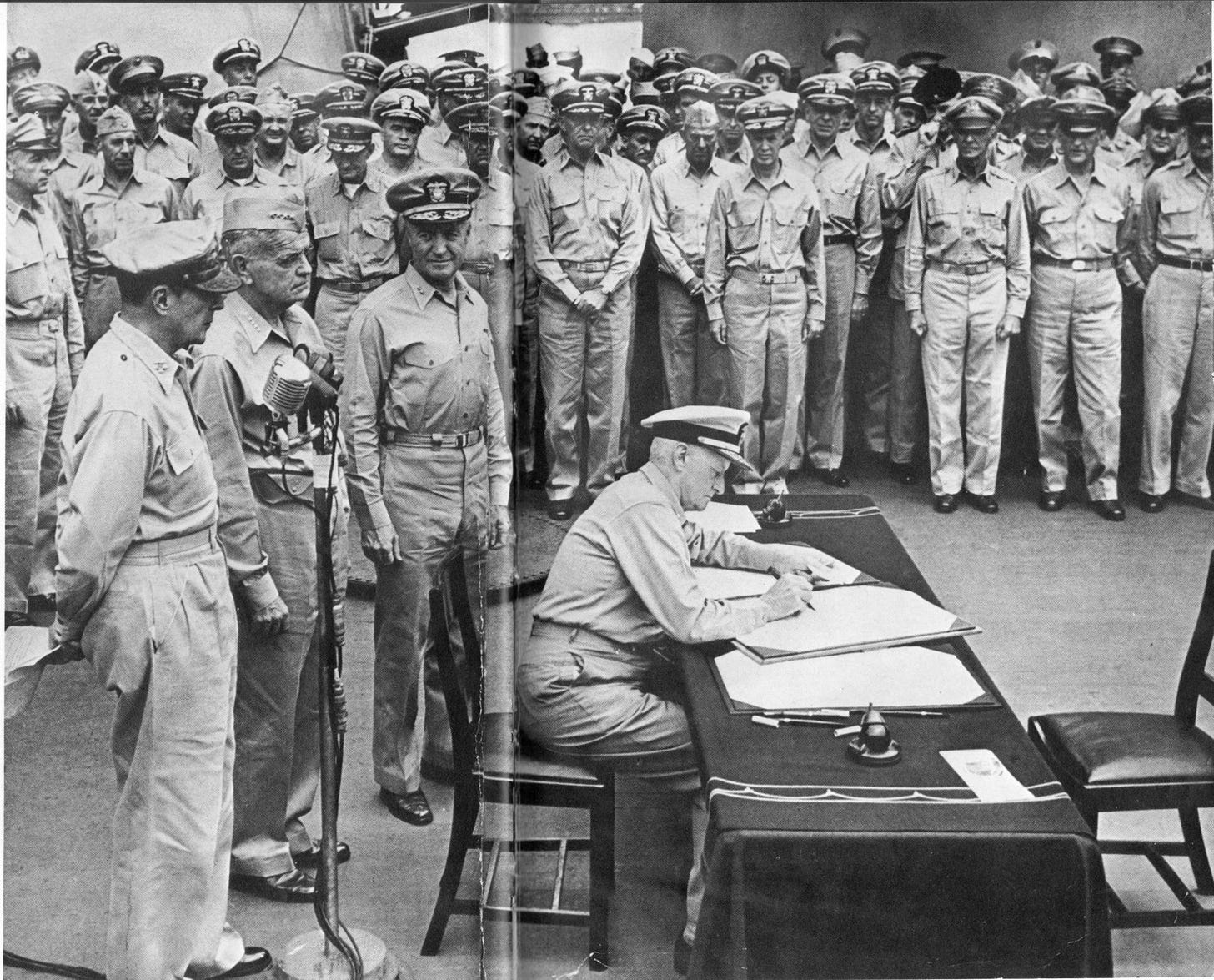

Admiral Nimitz, commander of US forces in the Pacific, signs the surrender document as General MacArthur (L) looks on.

Thanks to all who support That’s Another Fine Mess. Comments are for the Paid Subscribers who keep things going.

Somehow, this reminder of the Japanese surrender on the USS Missouri seems apt, after President Biden's stirring speech last night calling out Maga Republicans for what they are.

We now have to fight fascism at home, here in the U.S.A. Growing up, I would never have imagined it.

There is a victory ahead, a victory for freedom and democracy. If we can stick together.

Pick your battles. Work hard. And win elections.

How many carriers does it take to hold 680 airplanes? ( serious question) That is a great photo of all those planes. The logistics and accuracy it must have taken to get them all back to their respective carriers!!