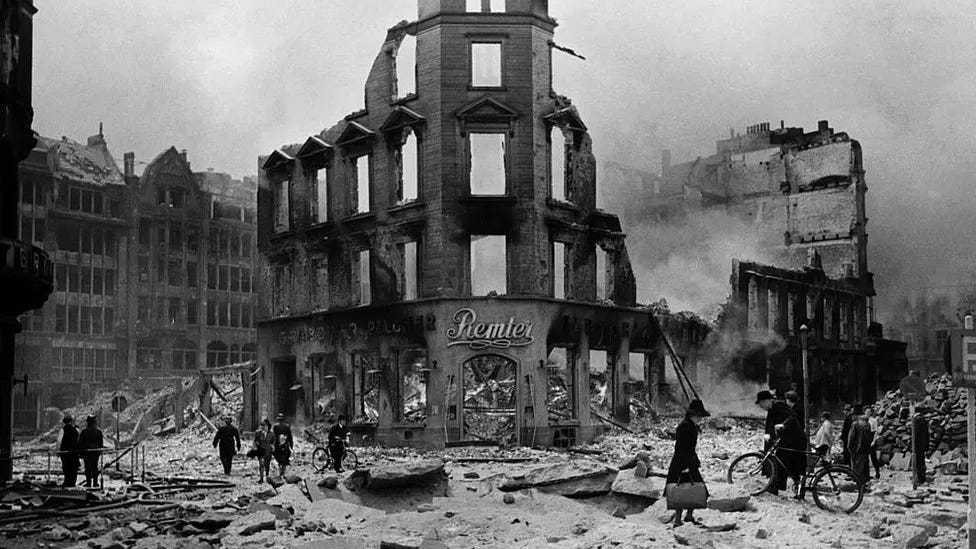

Hamburg street before the bombing

Among the targets hit in Little Blitz Week was Hamburg, which VIII Bomber command struck in collaboration with RAF Bomber Command in “Operation Gomorrah.” Hamburg’s shipyards produced U-boats, and its oil refineries were crucial for the German war effort. What made this operation different was it was the first to make widespread use of what the British called “Window” and the Americans named “Chaff.” This was bundles of aluminum strips, cut to the wavelengths of the German radars, as the bundles broke open after they were thrown out of the bombers, the foil strips floated to the ground. While they were in the air, they effectively blinded the German radars, which returned nothing but “snow.”

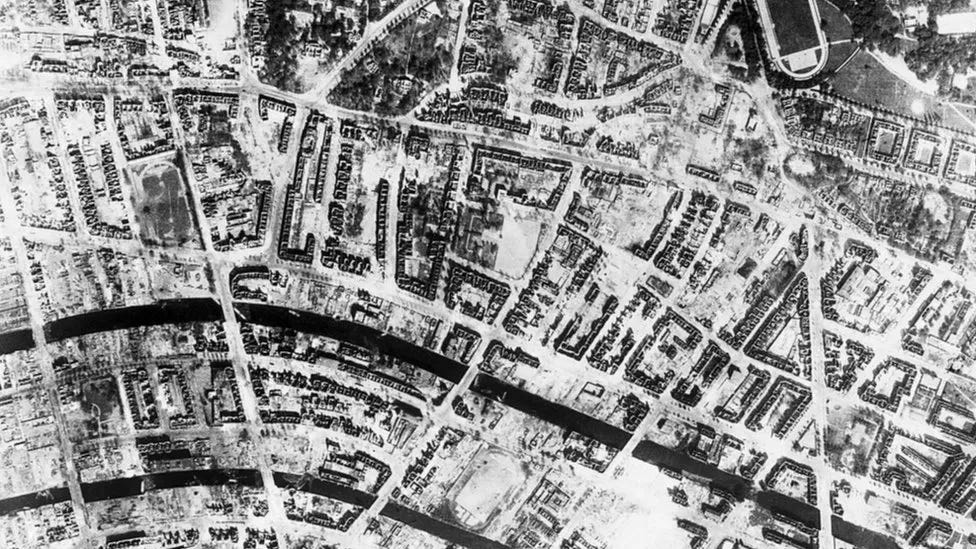

Hamburg damage

This meant that the German night fighters were completely unable to make any interception under radar guidance. While enemy fighters could spot the American bombers in daylight, the lack of radar vectoring meant the short-ranged German fighters used up crucial gasoline searching for their targets. Both sides had known how this worked conceptually for at least a year before, but neither had been willing to make use of the tactic since its success would inform the other side, which could then use it against the radars of the initiators. British losses at night had grown as the Kammhuber Line became more effective with its “Himmelbett” system of radar-guided interceptions, which prompted the decision to finally make use of the new weapon.

By July 1943, both the RAF and USAAF bomber commands in England were at the point of “put up or shut up.” They needed a major success. With an extended period of good weather forecast, Hamburg became the target. The bombers would drop incendiaries, aimed at the old medieval heart of the city, where building construction was largely of wood. The USAAF had just received a large supply of the new American-made oil-based incendiaries, which VIII Bomber Command believed was superior to the four-pound magnesium-cased thermite bombs used by the RAF. There would be multiple raids over a period of days to stoke the fires that the earlier raids started. Weather-wise, there had been little rain in previous weeks while the temperatures had been unusually warm. These conditions would allow the bombers to make highly-concentrated drops around the intended targets. The dry, warm air would create vortex and whirling updraft of super-heated air which resulted in a tornado of fire.

The City afterwards

Operation Gomorrah - named for the biblical city destroyed in a rain of fire and brimstone - began on July 24 and continued for eight days and seven nights. It was the most sustained bombing campaign to date.

A Lancaster bomber silhouetted over the fires

The first RAF raid began 57 minutes after midnight on July 24, and lasted for nearly an hour. The 40,000 firemen found their firefighting resources damaged when the telephone exchange caught fire; rubble blocked the movement of fire engines through the city streets. The fires raged out of control and were still burning three days later.

The first USAAF raid arrived over the city at 1640 hours the next day. While 300 bombers were supposed to participate, problems in assembly in poor weather over England meant only 90 bombers attacked the the Blohm and Voss shipyard and an Daimler-Benz aircraft engine factory; smoke from the fires made visual bombing difficult and the shipyard was only lightly damaged while a generating station was bombed instead of the factory, which was invisible in the smoke. German flak damaged 78 of the 90 attackers to varying degrees. The smoke was so thick that the planned bombing that night was canceled, with the RAF hitting Essen instead. The raid attempted the night of July 26 was not considered successful because of thunderstorms and high winds over the North Sea that caused bombers to abort. There was no USAAF raid that day, again due to poor visibility from the smoke of the still-burning fires from the first night.

Hamburg on fire

On the night of July 27, just before midnight, 787 British bombers began dropping incendiaries, with the main aiming points being the dense housing in the working-class neighborhoods of Billwerder, Borgfelde, Hamm, Hammerbrook, Hohenfelde and Rothenburgsort. The use of blockbuster bombs dropped in the early part of the raid prevented firefighters from getting to the scene quickly. The lack of firefighting and the dry, warm weather let the fires grow quickly, which culminated in a firestorm. The tornado of fire created an inferno, pushing the winds as high as 150 mph and reaching temperatures of 800 °C (1,470 °F), while the flames reach an altitude of over 1,000 feet. A total of 21 square miles of the city were incinerated. Asphalt streets caught fire, while fuel oil from damaged and destroyed ships, barges and storage tanks filled the canals and the harbor, which caught fire.

A firefighting crew overcome by the fire

Generalmajor Wilhelm Kehrl, chief of Haburg’s civil defense, reported, “Trees three feet thick were broken off or uprooted, human beings were thrown to the ground or flung alive into the flames by winds that exceeded 150 kilometers per hour, The panic-stricken citizens had nowhere to turn. Flames drove them from the shelters, but high-explosive bombs sent them scurrying back again. Once inside, they were suffocated by carbon-monoxide poisoning and their bodies reduced to ashes as though they had been placed in a crematorium, which was indeed what each shelter proved to be.”

A restored Hamburg shelter - these became crematoria for those who took refuge

RAF Bomber command attacked again the next night. The incendiaries merely kept the fires going. Thunderstorms over England led to cancellation of another USAAF raid during the next day, and the British bombers were kept on the ground by the rain that night. The last raid was made by the USAAF and RAF on August 3.

Areas of the city were sealed off after the survivors were evacuated

The death toll from Operation Gomorrah will never be certain, but by December 1, 1943, the official toll was 31,647 confirmed dead, but only 15,802 were based on actual identification of a body. The number of those who died in cellars and shelters could only be estimated from the quantity of ash on the floors.

The first week after the raid, approximately one million survivors were evacuated, since 61 percent of the city’s housing stock was destroyed or damaged. The work force was reduced by ten percent.

Aerial photo of the city after the raids

No subsequent city raid shook the German government the way Hamburg did. Josef Goebbels, who visited the city ten days after the raids, is said to have reported to Hitler on his return to Berlin that more raids like this would force Germany out of the war.

Industrial losses were severe: 183 large factories were destroyed of 524 in the city, while 4,118 smaller factories were destroyed of 9,068 total. The losses included severe damage to 580 industrial firms and armaments works. All local transport was completely disrupted and did not return to normal during the rest of the war. Hamburg would be bombed 69 times over the course of the remainder of the war, preventing any real recovery. As late as 1955, the city was still being rebuilt.

A week after the last raid

In the censored German media, the Hamburg raids were seen as being far worse than the major military reverse that had taken place over the course of July in the Battle of Kursk on the Eastern Front or the loss of Sicily the same month. An August 9 report by United Press carried an account by a Swiss merchant who had been in the city, stating that "Hamburg's ceaseless, inescapable destruction is on a scale that defies the imagination."

On August 27, a month after the attacks, the city was still afire. Heinz Knoke went flying for the first time since being wounded back in June. He took the unit’s Bf-108 “Taifun” hack and flew to Hamburg. What he saw left a strong impression when he wrote in his diary later:

“During my flight I observe the great fires that are still raging everywhere in what has become a vast area of rubble. A monster cloud of smoke rises up to 3,000 meters above the fires, fanning out to a width of some 10 to 20 miles, as it slowly drifts eastward to the Baltic Sea, 70 kilometers away. There is not a cloud in the sky. The giant column of rising smoke stands out starkly against the summer blue. The horror of the scene makes a deep impression on me. The war is assuming some hideous aspects. I resolve with grim determination to return to operations in spite of my wounded hand.”

In the next two years, Hamburg’s 35,000 would be joined by the deaths of 25,000 in the fire bombing of Dresden and the almost-unimaginable loss of more than 100,000 in one night to a firestorm set by B-29s on March 9-10, 1945 in Tokyo.

A week after Tokyo, the port cities of Kobe-Osaka became the second great firestorm, killing over 90,000. Twenty years later to the day, during my first visit to Japan in the Navy, I became an unwitting witness to that event when my buddy and I - lost in the city - turned a corner and came face to face with what I later learned were the last 1,000 acres of unrestored Kobe. It was like staring into a black hole; in the sunset, there was no light reflected. The ground was still black, there were a few tumbled ruins, a girder stuck out of the ground. I thought I was looking at the cover art of a 1950s science-fiction novel about World War III. Sixty years later, that image has never left my memory. In the 1970s, the late Tom Bell became my aerobatics instructor in Sacramento. He had flown the lead B-29 of his squadron at Tokyo, Kobe-Osaka, and the other fire raids. He told me that from 5,000 feet above the cities, the smell permeated his bomber and was so overpowering that every man in the crew threw up; it could never be entirely cleaned out no matter how hard they tried. After the war, he could never attend a barbecue, because of the smell. USAAF and RAF crews who bombed Hamburg were the first to report this phenomenon.

But Hamburg shocked the senses because there was nothing before it to compare.

The same city street after the bombing

This account is excerpted from “Clean Sweep: VIII Fighter Command Against the Luftwaffe 1942-45.” This is an example of the “paid subscriber only” special posts that will be available behind the paywall at TAFM after August 1.

If you find That’s Another Fine Mess valuable, please consider becoming a paid subscriber for only $7/month or $70/year.

Comments are for paid subscribers only.

My grad school office-mate was a young child in Hamburg and could retell the horrifying experiences of watching everything around them melt from the intense heat, including family members who were overcome by the smoke. An indelible memory for him that I acquired and which contributed to my abhorrence of wa for what it is, an uncivil enterprise dressed up as some necessity by men with power and goals. No conventions can make warfare just or good or honorable. Your account today, and my Fred's experience, shows it for what it is. Vile, violent, murderous, and the victims, children and complicit adults and "good people" telling of it's necessity while mourning their personal losses. Thugs rob you in the streets, statesmen rob us of our children in the name of some holy cause or some national imperatives. Sadly, the thugs may be the more honorable of the two for they only take what you have on you, not the generations of children who will never come forward.

TC, your vivid report of Operation Gomorrah reminded me of the theme behind your SUMMER OF CLIMATE COLLAPSE?, in which you referred to Robert Oppenheimer, and the destruction we can bring to the human race. Your picture ‘A firefighting crew overcome by the fire’ in this piece reminded me not only of war but also of the Climate Crisis, which we have, again, brought on ourselves.