B-17s over the target

The sky over the English Channel at mid-day on July 28, 1943 was partly cloudy, an early indicator that the past week of clear weather over northwestern Europe was coming to an end. Fifteen miles west of the Dutch coast, the 40 olive drab and grey, white-nosed P-47 Thunderbolts of the 78th Fighter Group eased their slow climb out of England behind them to 23,000 feet and leveled off to cross into enemy air space ahead. Each big fighter carried a bulbous tank attached to its belly beneath the semi-elliptical wings. Standard Operating Procedure was for the fighters to make their entry into the enemy’s air at 29,000 feet, above the flak. But this time, 84th Fighter Squadron CO Major Gene Roberts - who led the formation - was attempting something new. He recalled, “We started with the usual 48 fighters - three squadrons of 16 fighters per squadron. However, two of the pilots reported mechanical problems and had to abort as we crossed the English Channel. In each case, per our standard procedure at that time, I had to dispatch the aborting airplane’s entire flight of four to provide an escort back to base. That left us with 40 fighters for the mission by the time we reached Holland.”

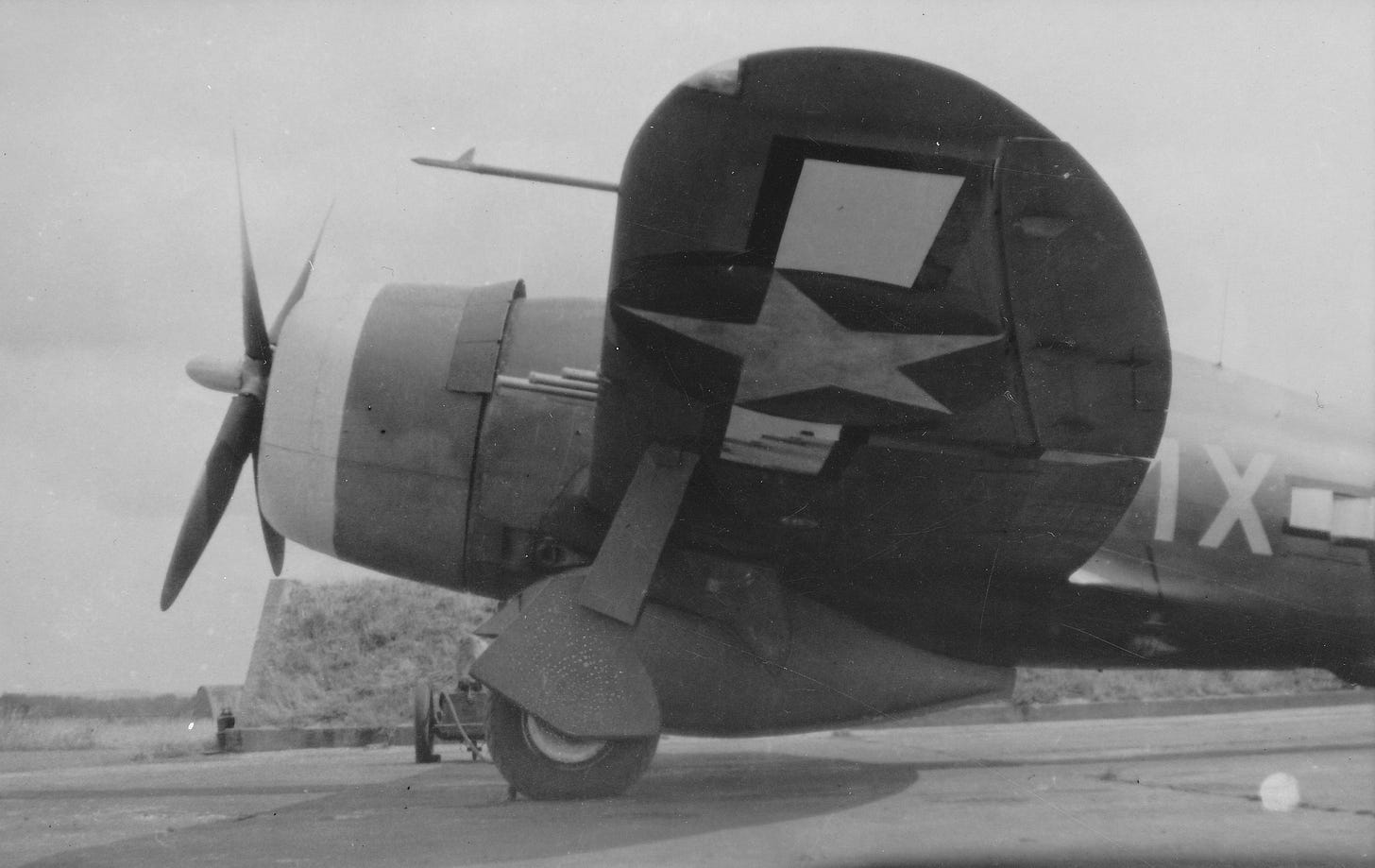

Gene Reynolds’ P-47C “Spokane Chief”

At this altitude, Reynolds reckoned the Thunderbolts could draw the last of the fuel from the unpressurized ferry tanks they carried. For a fighter that was as thirsty for fuel as the P-47, every gallon mattered, as the pilots attempted to get as far into enemy territory as possible. The Thunderbolts crossed the coast north of Rotterdam, high enough the sound of their roaring Pratt and Whitney 2,000-horsepower R-2800s was unheard on the ground below. They flew past Nijmegen, where the pilots switched to their internal fuel tanks as they pulled back on their sticks and followed Roberts up to 29,000 feet, where they leveled off and entered German air space over Kleve. From this altitude, they could see the city of Haltern on the horizon. Roberts thanked the lucky tail wind they must have found for pushing them so far east. This was the deepest penetration of Germany yet made by VIII Fighter Command fighters. Only the day before, the Fourth Fighter Group had used the troublesome belly tanks for the first time to set a new penetration record , making it as far east as the German border. Roberts’ decision to delay climbing to penetration altitude as long as possible was proven right as - for the first time ever - American fighter pilots looked down from their cockpits on western Germany. Their mission was withdrawal support to bring the bombers out of Germany.

P-47C with unpressurized ferry tank

Good summer flying weather in the latter part of July 1943 had allowed VIII Bomber Command to mount 14 strikes ever deeper into Germany since July 24, the first sustained air offensive by the Eighth Air Force against Germany proper since the Americans had commenced operations from southern England a year earlier. Eighth Air Force leaders saw it as the opening blow of the Combined Bomber Offensive that would over the next ten months prepare the way for the cross-Channel invasion and the liberation of Europe. The seven days of good weather would be known among the aircrews afterwards as “Little Blitz Week.” Today, July 30, the “blitz” would end with three missions against the Focke-Wulf factories at Oschersleben, Warnemunde and Kassel respectively. They were deep penetration missions beyond the range of escort fighters, and drew maximum opposition from the German defenders.

P-47s ready for takeoff at Duxford

One group of bombers executed a feint in the direction of much-bombed Hamburg-Kiel, then swung inland toward Oschersleben, 90 miles south-southwest of Berlin. Despite a cloud deck over the target, 28 B-17s bombed the AGO Flugzeugwerk, a major Fw-190 producer when a small hole in the nine-tenths cloud cover opened and the lead bombardier was able to recognize a crossroad only a few miles from the aiming point. Calculating quickly, he dropped by timing the flight to their ETA. The next day, reconnaissance photos showed a tight concentration of hits on the target. British intelligence estimated the attack, despite being only 67.9 tons, resulted in four weeks' loss of production. The Flying Fortresses were able to head into the westerly wind at 22,000 feet, thankful the wind allowed them to continue straight on for home. As the bombers came out of the flak field over the city, defending German pilots in Bf-109s and Fw-190s slashed through the bomber boxes. Three Fortresses were hit, catching fire and heading down. The sky filled with blossoming parachutes. A B-17 in the lead box took hits in an engine and dropped below, out of formation; the pilot added power to the three engines left as he desperately tried to keep up with the squadron for protection.

Charles London’s P-47C “El Jeepo” over the English Channel

At that moment, the 78th arrived on the scene. Roberts spotted the enemy fighters. “We were outnumbered by at least three-to-one odds but were able to maneuver into attacking position with very little difficulty. The main reason for this success was that the German fighter pilots didn’t believe we could possibly show up that far inland and were not expecting to see a defensive force at all.”

The American pilots took full advantage of German confusion. Roberts remembered: “There was one B-17 beneath the main formation, and it was being attacked by around five German fighters. The bomber was pouring smoke and appeared to be in deep trouble. From my position in the lead of the group, I dove down on the enemy fighters that were attacking the cripple. However, the Germans saw us, broke away, and dived for the ground. There wasn't much more we could do to help the crippled B-17, so I pulled up on the starboard side of the main bomber formation, about 1,000 yards out. I discovered on reaching this position that my second element — Lieutenant Colonel McNickle and his wingman — had broken away and was no longer with me. I had only myself and my wingman, Flight Officer Glenn Koontz. We immediately saw enemy aircraft ahead of us and above the formation. I judged that there were over 100 enemy aircraft in the area, as compared with our forty.”

Captain Charles London awarded the DFC as first P-47 ace

Roberts and Koontz came across a gaggle of Focke-Wulfs. “Dead ahead of me was a single Fw-190, at the same level as Koontz and me, about 1,000 to 1,500 yards ahead. He was racing in the same direction as the bombers so he could get ahead of them, swing around in front, and make a head-on pass. The bombers were most vulnerable from dead ahead. The Germans referred to this tactic as ‘queuing up.’”

Roberts dove slightly below the enemy fighter to avoid being spotted, then closed to 400 yards and opened fire, hitting the German heavily with a 3-5 second burst. “The Focke-Wulf's wheels dropped and it spun down in smoke and flames.” Roberts spotted two more. “They were about 2,000 yards in front of me, heading out so they could peel off and come back through the bomber formation.” Roberts closed so fast he had to pull up and roll in on his second victim to avoid a collision. “I opened fire from dead astern. I observed several strikes and, as before, the enemy fighter billowed smoke and flames, rolled over, and spun down.” Amazingly, Roberts and Koontz were still in the middle of the action.

“After the second engagement, we were about two miles ahead of the bombers, about 500 feet above them, and still well out to their starboard side. Koontz was on my right wing. About this time, I observed a 109 on the port side and ahead of the bomber formation. I dropped below the bomber formation, crossed over to the port side, and pulled up behind him, again at full throttle.” As Roberts closed on this third enemy fighter, the 109 suddenly executed a starboard 180-degree turn to attack the bombers head on. Roberts followed as the bomber formation loomed beyond the German. “I closed to within 400 or 500 yards and opened fire. He was in a tight turn, and that required deflection shooting. My first two bursts fell away behind him, but I continued to close. I fired my third burst as he straightened out to approach the bombers.” This caught the enemy fighter from dead astern within 150 yards of the bombers; it fell over into a spin, trailing smoke and flame. While Roberts dispatched his third victory, wingman Koontz flamed the wingman Roberts had failed to spot.

“We were now at the same level as the bombers and approaching them from head-on. We had no alternative but to fly between the two main formations, which were about two miles apart. Bless their hearts, they did not fire”’ Roberts then spotted two 109s attacking a P-47. “They were all heading 180 degrees to me, so I couldn’t close effectively to help. I did fire a burst at the leading German, but without enough deflection. The P-47 dove and took evasive action. I didn't see him or the Germans again. I headed out and joined up with a loose element from the 84th, and we headed home together.” Gene Roberts had just scored the first triple victory by an 8th Air Force fighter pilot.

Everyone else was equally busy. Group top-scorer Charles London caught two Fw-190s at 26,000 feet, flaming the leader and diving to avoid the wingman. Zooming back up to 28,000 feet he spotted a Bf-109 and hit it in its engine, setting it afire. With this victory, London was the first VIII Fighter Command ace and first to score all fivevictories in the P-47.

Captain Jack Price came across a flight of Fw-190s and flamed the leader. He then turned into the enemy element leader and opened fire with his wingman 2nd Lieutenant John Bertrand; each hit one of the three remaining 190s, which went down out of control.

Lt. Colonel Stone hit a Bf-109 that blew up so close that his wingman, 2nd Lieutenant Julius Maxwell, flew through the explosion.

82nd squadron commander Harry Dayhuff spotted a Bf-109 making a beam attack on the bombers; closing astern, the German blew up under his fire.

Suddenly, the sky was clear of enemy fighters.

P-47 escort from a B-17

The battle had been an intense ten minutes and the Thunderbolts broke off while they still had gas to return to their Duxford home. No more B-17s were lost after the 78th’s P-47s engaged. The bombers were soon picked up by the Fourth Fighter Group and taken home safe.

For a cost of seven P-47s lost in the melee, the 78th was credited with 16 victories. Added to the eight credited to the 56th and Fourth Groups, the day’s battles doubled VIII Fighter Command’s total score to date. Charles London had become an ace, while Gene Roberts had scored the first “triple.”

Overall, the missions cost 22 B-17s and their crews, with the force sent to Oschersleben losing 15 of the 39 that bombed the target. Claims by the defending gunners bore witness to the intensity of the fighting, with the Oschersleben force claiming 56 enemy aircraft destroyed, 19 probably destroyed, and 41 damaged; all claims from both groups totaled 83/34/63.27. The Jagdwaffe’s actual loss was 15, which was primarily due to the intervention of the 78th’s P-47s.

July 30, 1943 is the most important date in the history of VIII Fighter Command. For the first time, American fighters found and attacked superior enemy fighter forces over Germany, scored heavily with minimal losses, and protected the bombers. It was the sign of things to come.

This excerpt from “Clean Sweep: VIII Fighter Command Against The Luftwaffe 1942-45" is an example of some of the special “paid subscriber only” posts that will be available behind the TAFM paywall after August 1.

If you find the material here interesting, you can support That’s Another Fine Mess by becoming a paid subscriber for only $7/month or $70/year.

Comments are for paid subscribers only.

You know the writing is good when it reads just as well the second time.

Amen Dave. Great read always on any topic. Great selection of photos too! Now I'm addicted to TC's WW II books! The hook was the Tonkin Gulf Yacht Club!