Task Force 38 Off the Coast of Japan

The first quarter moon hung in the western sky gleaming dimly through scattered clouds over the Pacific; the moonlight sufficient to illuminate the many wakes of the huge formation of ships below. At 0300 hours, an observer would have heard the calls to reveille echoing across the still-dark sea throughout the darkened fleet.

In the big boxy aircraft carriers that steamed in the center of the formations, crewmen crawled out of their racks in humid bunking compartments and began pulling on their dungarees; young pilots stumbled to their feet in their cramped staterooms and threw lukewarm water on their faces to awaken fully before staggering off to the wardrooms for a quick breakfast. The fleet had sortied from Leyte Gulf in the Philippines on 1 July for what would turn out to be their final deployment of the war, and the limited supplies of fresh food taken aboard then were running out now, six weeks later. Spam sandwiches and the chipped dried beef in gravy over toast known universally as “SOS” (“shit on a shingle”) were once again making their appearance on the menu. Below decks, enlisted men shuffled through chow lines.

The wail of alarms across the fleet brought crews to pre-dawn General Quarters. Men tumbled into the gun tubs and unlimbered 20 mm and 40 mm anti-aircraft guns in readiness as they strained their eyes into the western sky where the Pacific sunrise lit building cumulus clouds in all quarters. The fleet had not been subjected to kamikaze attack in several days and was just returning from a day spent out of range, while the carriers refueled their thirsty escorts. Would today be the end of that pause?

It was Wednesday, 15 August 1945, just another of many long tiring days faced by the men of the United States Third Fleet. In recent days, rumors had raced through the destroyers, cruisers, battleships and aircraft carriers of the mightiest fleet the world had ever seen that the war could end at any time. Those who passed on the rumors were quickly reminded by their salty seniors of the old navy saying, “Believe nothing that you hear, and only half of what you see.”

Task Group 38.4, commanded by Rear Admiral Arthur W. Radford with his flag aboard USS Yorktown (CV-10) and composed of the fleet carriers USS Shangri-La (CV-38), Bon Homme Richard (CV-31), and Wasp (CV-18), accompanied by the light carriers USS Independence (CVL-22) and Cowpens (CVL-25), exemplified the fast carrier striking force in the summer of 1945. Centered around six carriers, it was numerically the strongest task group in Task Force 38. The squadrons aboard the six carriers included a total of 133 Grumman F6F-5 Hellcats, including 36 dedicated night fighters aboard “Bonnie Dick”; 137 Vought F4U Corsairs, including 36 brand new F4U-4’s, aboard Wasp; 45 Curtiss SB2C Helldiver dive bombers including 15 of the latest SB2C-5 aboard Wasp; and 80 of the newest TBM-3 Avenger torpedo bombers. Able to strike the enemy by day or night, Task Group 38.4 packed more punch than the entire pre-war carrier force combined. Altogether, Task Force 38 was centered around ten fleet carriers and six light carriers in three task groups.

Aboard USS Yorktown (CV-10), veteran of the early days of the Central Pacific Campaign that had taken the fast carrier force from a tentative raid on Wake Island by four carriers only twenty-two months earlier to regular strikes against targets on Honshu and Hokkaido islands since 10 July, the young pilots of VF-88 - Fighting-88 - made their way to the squadron ready room for the morning briefing. Air Group 88 was one of the newest in the fleet, having only come aboard Yorktown at Leyte the past June while the fleet licked its wounds and caught its breath after the battle of Okinawa, site of the worst losses since the early days in the Solomons three years before. VF-88 had taken heavy losses in the six weeks since Admiral Halsey had brought the fleet to the waters off Japan, with ten pilots now gone, including squadron leader LCDR Charles Crommelin, lost in a freak midair collision with his wingman over Hokkaido 30 days earlier - the last of four legendary brothers to die in the Pacific War.

The pilots were unsure of Lieutenant Malcolm W. Cagle, the former squadron executive officer who now led them; the combat-experienced division leaders who had joined the squadron during training in the past year doubted that Cagle, who hadn’t become a Naval Aviator until 18 months earlier and whose flying experience had been confined to the Training Command until he was given the plum position of squadron XO, could fill Crommelin’s shoes. These experienced men were AvCads - reservists commissioned for the duration of the war after graduating from flight school - while Cagle was a “ringknocker,” an Annapolis graduate. They knew that as a “regular” Cagle was the beneficiary of the rule, “The Navy takes care of its own.” Today, Lieutenant Cagle’s leadership ability was in doubt. When the popular Crommelin went down and Cagle became the commander, he told the pilots that if they had any suggestions, he’d like to hear them; no one replied, since as one recalled, “We observed body language that said ‘I don’t want to hear it.’”

The squadron’s assignment this morning wasn’t that different from previous missions, but the men were electrified by Cagle’s announcement that the Japanese were likely to surrender today, though the exact time was not yet known. The mission was to prevent an aerial Banzai attack by any Japanese fliers who refused the orders of their Emperor to surrender. Two divisions - eight F6F-5 Hellcats - would join up with eight other Hellcats from Wasp’s VF-86 and a further sixteen F4U-1D Corsairs from Shangri-La’s VF-85 and VBF-85 to attack airfields in the vicinity of Choshi, the easternmost city of greater Tokyo. The eight Fighting-88 Hellcats were to split into two groups when they reached Tokurozama airfield. Two pilots would stay high to receive and relay the hoped-for cease-fire message that might be broadcast at any time. The others - Lt(jg)s “Howdy” Harrison, Maury Proctor, and Ted Hansen, and Ensigns Joe Sahloff, Wright Hobbs, and Gene Mandenberg - would strafe anything they found on the airfield. Launch was set at 0430 hours.

Takeoff for Task Force 38 on this last day of war commenced just as the sun appeared over the eastern horizon, though the sea was still dark. Throughout the fleet, pilots lifted off their carriers and climbed up into the morning light, each man hoping that the recall order might come before they arrived over the enemy coast.

Leading the Fighting-88 Hellcats inbound to Choshi, Division leader “Howdy” Harrison spotted the great volcano Fujiyama, its snow-capped peak gleaming in the early morning light high above the Tokyo plain and the waters of Tokyo Bay. The seven other Wasp Hellcats and the sixteen Shangri-La Corsairs were dark silhouettes in the brightening sky. High clouds were now visible in all directions.

Atsugi airfield east of Tokyo was the main base for the Imperial Naval Air Force in the capital region and was home to the 302nd Kokutai (air group), one of the last remaining elite units of the Imperial Japanese Navy. The group had been created in March 1944 to provide defense for the capital against the expected B-29 raids.

Commander of the 302nd was 23-year old Lieutenant Yukio Morioka, the youngest Japanese air group leader of the war. Originally trained as a dive-bomber pilot in 1942, Morioka had missed the great carrier battles and had taken the opportunity to become a fighter pilot in the spring of 1944 when he was assigned to the 302nd. On 23 January 1945, Morioka had nearly died when a gunner aboard a B-29 of the 73rd Bomb Wing he was attacking shot off his left hand. It was considered a miracle that he had been able to land successfully despite shock and loss of blood. After a brief stay in the hospital, he was fitted with an iron claw with which he could control the throttle of his fighter, and returned to combat in April. As of this morning, he was the victor over four American aircraft.

Upon receipt of the warning that enemy planes had been spotted,Morioka took off quickly with his wingmen, Ensigns Mitsuo Tsuruta, Muneaki Morimoto and Tooru Miyaki, close behind and followed by a second flight of four Zeros as they climbed into the brightening sky.

At 0645 hours, the VF-88 Hellcats and their Shangri-La shipmates were over the target. “Howdy” Harrison led his six Hellcats low over Tokurozama just as the word was passed that the Japanese had surrendered. Ted Hansen recalled thinking, “Oh God, let’s get our fannies out of here.”

The six Hellcats were hit seconds later from behind and above by 17 Japanese fighters. Turning into the attackers, Harrison opened fire. In the opening head-to-head pass, Hansen shot down one that tried to ram him and splashed a second. A third lost its wing to Maury Proctor’s fire. Losing track of Mandenberg, Harrison, and Hobbs, Hansen and Proctor joined up and soon spotted a Jack on Joe Sahloff’s tail which Proctor exploded. Clearly in trouble with his fighter trailing smoke, Sahloff turned for the coast but was never seen again.

As Proctor turned away, he was bracketed with tracers. He made a tight right turn that gave Hansen the shot to nail the fighter on his tail. As he reversed course, Proctor saw two other enemy fighters on fire. More importantly, six others in front of him and one turning behind him were still full of fight. He managed a killing belly shot when the formation of six pulled into a climb, then quickly ducked into a cloud to evade the one behind. When he popped out moments later the sky was empty. As he flew toward the coat, he attempted to contact the others and thought he heard Hansen. Hansen heard nothing and thought he was the sole survivor until Proctor appeared overhead five minutes after he trapped aboard Yorktown.

The fight over Tokurozama went into the historical record as the war’s last substantial air battle. While the six pilots claimed nine kills, it came at the high cost of four missing and finally listed as presumed dead: Harrison, Hobbs, Mandenberg, and Sahloff.

While Japanese records are incomplete as to which units were engaged where on this last day of the war, 302nd Kokutai commander Lieutenant Morioka claimed he shot down one of six F6F Hellcats the 302nd came across “near Atsugi,” which is very close to the reported location of the VF-88 Hellcats when they were hit.

At noon, while the men aboard the ships of the Third Fleet celebrated their survival, the Japanese people heard a voice almost none had ever heard before - the voice of Emperor Hirohito, announcing that the war “had not gone as expected” and telling his people it was over.

It was still unclear if the Japanese military would follow the order of their emperor. At the same time the Emperor spoke, VF-31 launched four divisions of Hellcats - sixteen fighters - to relieve the Combat Air Patrol over the task group. At 1400 hours, radar aboard USS Lexington (CV-16), flagship of Task Group 38.1, picked up a lone bogey closing the fleet. Admiral Halsey gave the order “Shoot it down, not with hostility but with compassion”.

Ensign Clarence Moore spotted the intruder and identified it as a Judy, the American code name for the Yokosuka D4Y3 Suisun (Comet) dive bomber that was the most commonly-used kamikaze attack aircraft. Ensign Moore turned in behind the Judy and set it afire with two short bursts of fire. The Judy crashed into the ocean below, the last Japanese aircraft shot down by a U.S. Navy fighter pilot in the Pacific War.

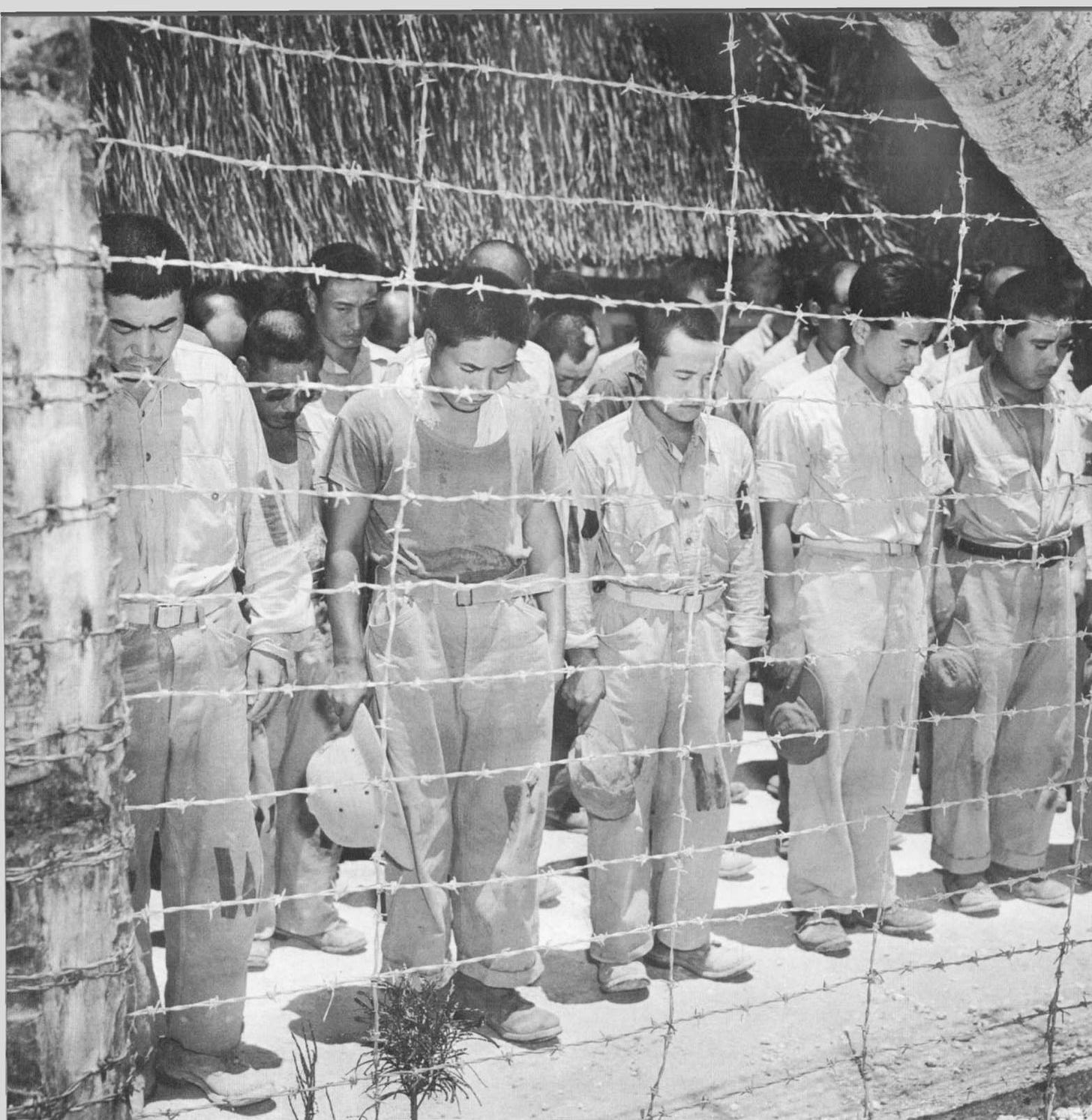

Japanese POWs hear the news of Japan’s defeat

Please consider supporting That’s Another Fine Mess by becoming a paid subscriber for only $7/month or $70/year.

Comments are for paid subscribers.

Speaking of remembering - something far too many of us are unaware of.

The 761st Tank Battalion - all black men - Morgan Freeman is doing a documentary - it took decades for these men to get the medals & awards they earned! Sound familiar?

Yet another piece of US history that doesnt show up in the history books!

“Shoot it down, not with hostility but with compassion.” Thanks, TC.