THE FORGOTTEN BOMB

The Nagasaki Bomb’s Mushroom Cloud

In the popular imagination of the war, Nagasaki is almost forgotten while Hiroshima stands center stage. That may well be because at the time of the attack, the Americans did not know what they had destroyed. It is a supreme irony that Nagasaki was (and is) the most pro-Western, anti-Imperial city in Japan, the center of Christianity in that country since its introduction by the Dutch and Spanish in the 16th century and because of that fact the center of resistance to the Tokugawa Shogunate when Japan was closed to the outside world for 200 years commencing in the 17th century. The city was where Giacomo Puccini wrote the opera “Madame Butterfly” while he lived there in a beautiful cottage on a hill overlooking Nagasaki Bay (which I visited).

Nagasaki harbor on August 1, before the bomb

9 August 1945 was cloudy over most of mainland Japan as a result of the lingering effects of the typhoon that had passed several days earlier, as well as the monsoonal weather.

On the island of Tinian in the Marianas, a B-29 Superfortress of the 393rd Bombardment Squadron, Heavy, 509th Composite Wing, named “Bockscar,” commanded by Major Charles Sweeney, took off from North Field at approximately 0347 hours local time, just before dawn; the bomber was seriously overloaded and used nearly every inch of the 8,300-foot runway to get airborne. It headed almost immediately into heavy weather. The first mission had been easy; this mission would be the opposite.

Sweeney and his crew had previously flown “The Great Artiste” which carried the instrumentation to record the mission of the B-29 “Enola Gay” on the Hiroshima mission of 6 August. This second mission had been scheduled for 11 August, but a forecast of bad weather pushed the schedule forward and Sweeney was now flying the B-29 usually assigned to Captain Frederick C. Bock since there had not been time to remove the additional instrumentation from “The Great Artiste.” Despite the discovery during pre-flight inspection that a fuel tank would not feed, Sweeney felt he had no alternative but to proceed with the mission, despite not being able to use a fourth of the fuel on board.

“Enola Gay” had deployed an atomic bomb using uranium-238 for the explosive, known as “Little Boy.” “Bockscar” carried a plutonium bomb named "Fat Man" which was far more powerful than “Little Boy.” The primary target was the industrial city of Kokura, home of the largest munitions plants in Japan. During the nearly eight-hour flight, monsoon winds, rain, and lightning lashed at the bomber; St. Elmo’s fire played along the wings and spinning propellers. Along the way, Sweeney discovered that their climb to a higher altitude to deal with the weather had increased fuel consumption.

“Bockscar” - the Nagasaki Bomber

Inside, the crew experienced a moment of terror around 0700 hours, halfway to Japan when the bomb began to arm itself with a red light blinking with increasing rapidity on the weapon panel. It was possible it could now explode if they lost altitude. Navy Commander Frederick L. Ashworth, the weaponeer in charge of the bomb, grabbed the blueprints and crawled into the bomb bay with his assistant weaponeer, Lieutenant Philip M. Barnes, to figure out what was going wrong. The two removed the bomb’s casing and scrutinized the switches. After a tense ten minutes, Ashworth saw the problem. During the arming process, two switches had been reversed by mistake. Barnes flipped the two tiny switches to their correct positions. The red light stopped blinking.

At 0900 hours, they arrived off the Japanese coast at 30,000 feet. The bad weather prevented a rendezvous over Yakushima, an island off the southern tip of Japan, where they were to meet the escorting photo B-29 “Big Stink,” flown by Major James I. Hopkins, and “The Great Artiste,” flown by Captain Bock. At 0910 hours, Bock made the rendezvous but “Big Stink” was nowhere to be seen. Unbeknownst to the others, Major Hopkins was orbiting 9,000 feet above, searching for them. Sweeney circled for 15 minutes, then 30 minutes, then for 45 fuel-burning minutes. Valuable time, and more importantly valuable gasoline, was lost. Finally, the two B-29s headed toward the target. High above, Hopkins, frantic over the failed rendezvous, broke radio silence and radioed Tinian, asking (in code) "Is Bockscar down?"

The Nagasaki Bomb 15 minutes later

On Tinian the transmission’s first word was dropped. They heard: “Bockscar down.” Despair settled over the 509th’s base of operations at North Field. They believed they had lost the weapon that was finally going to end the war.

“Bockscar” arrived over Kokura at 0944 hours local time (1044 hours Tinian time). Sweeney and his crew discovered that visibility was obscured by clouds and smoke coming from the nearby city of Yawata, which had been firebombed the previous night. Their orders regarding deployment of the bomb were specific in that it was only to be dropped visually. “Bockscar” made three runs over the city, but the bombardier, Captain Kermit Beahan, could not find clearance for a visual drop. As the B-29 finally pulled away flak burst all around; Kokura was one of the most heavily-defended cities in Japan. By 1030 hours local, the gas gauges were tipping toward half-full when Ashworth convinced Sweeney to proceed to the secondary target.

“Bockscar” arrived over Nagasaki 20 minutes later, at 1050 hours. Again, the city was obscured by clouds. The B-29 was now desperately short of fuel and it was soon apparent that they had no hope of returning direct to Tinian and would have to make an emergency landing on Okinawa to refuel. Again, they flew across the city on two fruitless bomb runs.

Sweeney turned for the third run. The fuel situation was now critical - he could now only make it to Okinawa without the bomb aboard. If it couldn’t be dropped visually, the only choice would be to jettison it over the ocean. Charles Sweeney was not about to be the man who returned to inform his superiors that he had dropped the most important, most expensive, most valuable weapon of war ever created to lie unused on the seabed off Japan.

The Urakami Catholc Church afterwards

Commander Ashworth was convinced if they did not drop the bomb none of them would survive. He conferred with bombardier Beahan and told him he would take responsibility for the bombing and that Beahan should drop the bomb by whatever means he had. Beahan watched the radar screen. The unmistakable shape of the Mitsubishi Steel Plant in Urakami Valley came into view on the screen. Beahan opened the bomb doors. Ashworth told him “Use the radar.”

At the last moment, Beahan exclaimed that there was a hole in the clouds and he could bomb visually. Sweeney replied, “Okay, you own the plane.” Beahan had only 45 seconds to set up the bombsight, kill the drift, and kill the rate of closure on the target.

“Bombs away!”

At 1201:40 hours Tinian time, Fat Man fell from “Bockscar” and twenty seconds later at 1202 hours, it exploded 1,840 feet above the city with a force of 22,000 tons of TNT.

Inside the B-29, the crew were thrown around by several shock waves. Radar countermeasures officer 2nd Lieutenant Jacob Beser was pinned to the floor and thought the bomber would be torn apart.

Navigator 2nd Lieutenant Fred Olivi later described the mushroom cloud he saw out his window: “It was bright bluish color. It took about 45 or 50 seconds to get up to our altitude and then continued on up. I could see the bottom of the mushroom stem. It was a boiling cauldron. Salmon pink was the predominant color. I couldn’t see anything down below because it was smoke and fire all over the area where the city was. I remember the mushroom cloud was on our left. Somebody hollered in the back: ‘The mushroom cloud is coming toward us.' This is where Sweeney took the aircraft and dove it down to the right, full throttle, and I remember looking at the damn thing on our left, and I couldn’t tell for a while whether it was gaining on us or we were gaining on it.”

Urakami Cathedral aftet the bombing

At 1205 hours Sweeney pushed over into a second dive just in time to avoid flying through the cloud of atomic ash and smoke, which was still climbing into the upper atmosphere.

The two bombers turned south toward Okinawa in radio silence. “Bockscar” was so low on fuel they expected to crash at sea and everyone checked their Mae Wests. Back on Tinian, it was believed the mission had failed.

Sweeney had climbed to 30,000 feet and could now descend in a semi-glide with minimum fuel consumption. When they arrived five minutes out of Okinawa, there was heavy traffic moving to and from the runways. All fuel tanks read empty. Sweeney received no response to his emergency calls. He ordered flares to be fired. Olivi later wrote: “I took out the flare gun, stuck it out of the porthole at the top of the fuselage and fired all the flares we had, one after another. There were about eight or ten of them. Each color indicated a specific condition onboard the aircraft.”

So far as the men in the control tower were concerned when they saw that, “Bockscar” was out of fuel, on fire, had wounded men, and every other possible crisis.

With Olivi still firing off flares, “Bockscar” touched down on Yontan North airfield at 1351 hours local at 140 miles per hour, 30 mph too fast, as the number two inboard engine died of fuel starvation. The big B-29 bounced 25 feet into the air before settling down. The pilots both stood hard on the brakes and used the special reverse pitch on the propellers to slow down as they sped past rows of parked B-24 Liberators that were fueled and loaded with incendiary bombs. At the end of the runway, Sweeney made a full 180-degree turn and headed to a paved parking area; the plane was now rolling on fumes.

Ambulances, fire trucks, and other vehicles pulled up. Sweeney told the crew not to say anything about the mission. A jeep took Ashworth and Sweeney to headquarters, where Eighth Air Force commander LGEN James H "Jimmy" Doolittle, who had arrived on the island two weeks earlier, met them. He asked Ashworth, “Who the hell are you?” Ashworth replied “What the hell is wrong with your control tower? We are the 509, Bockscar. We dropped an atomic bomb on Nagasaki.”

“Bockscar?” replied the amazed Doolittle. “You’re not lost? Thank God you didn’t hit those B-24s. Just missed one hell of an explosion. Guess you already had one hell of an explosion.” He looked hard at Ashworth. “We heard you were down.”

Later, Doolittle remarked to a friend that the landing was “the scariest thing I ever saw.”

Three hours later, “Big Stink” arrived. Major Hopkins had circled Nagasaki and photographed the damage with an unofficial camera that a young physicist, Harold Agnew, had fortunately sneaked on board since no one on the plane could operate the official camera. At 1730 hours, the three B-29s departed Okinawa for Tinian, where they arrived at 2245 hours.

While “Enola Gay” had been greeted on her return with fanfare and praise, “Bockscar” was not. The Air Force did not push the story or decorate the crew, again unlike what happened with the “Enola Gay” crew. Some said Sweeney should be court- martialed for disobedience of orders, but nothing was done. By then, there was no point in bringing up a near catastrophe.

No one will ever know for certain if bombardier Fred Beaman really bombed visually at the last minute, or whether he followed Ashworth’s suggestion and used the radar. The bombardier always maintained afterwards that he had followed his instructions to the letter.

What is known is that what was seen on the radar screen was not the Mitsubishi munitions factory. It was the Urakami Catholic Church, the largest Christian church in all of Asia, built in the decades following the legalization of Christianity sixty years earlier, through the donations of the parishioners who were the descendants of the Shogun-hating Kakure Kirishitan. The downward force of the explosion flattened every part of the church other than the bell tower, which was directly beneath the center of the blast and immediately became the only structure still standing at what would come to be known as Ground Zero.

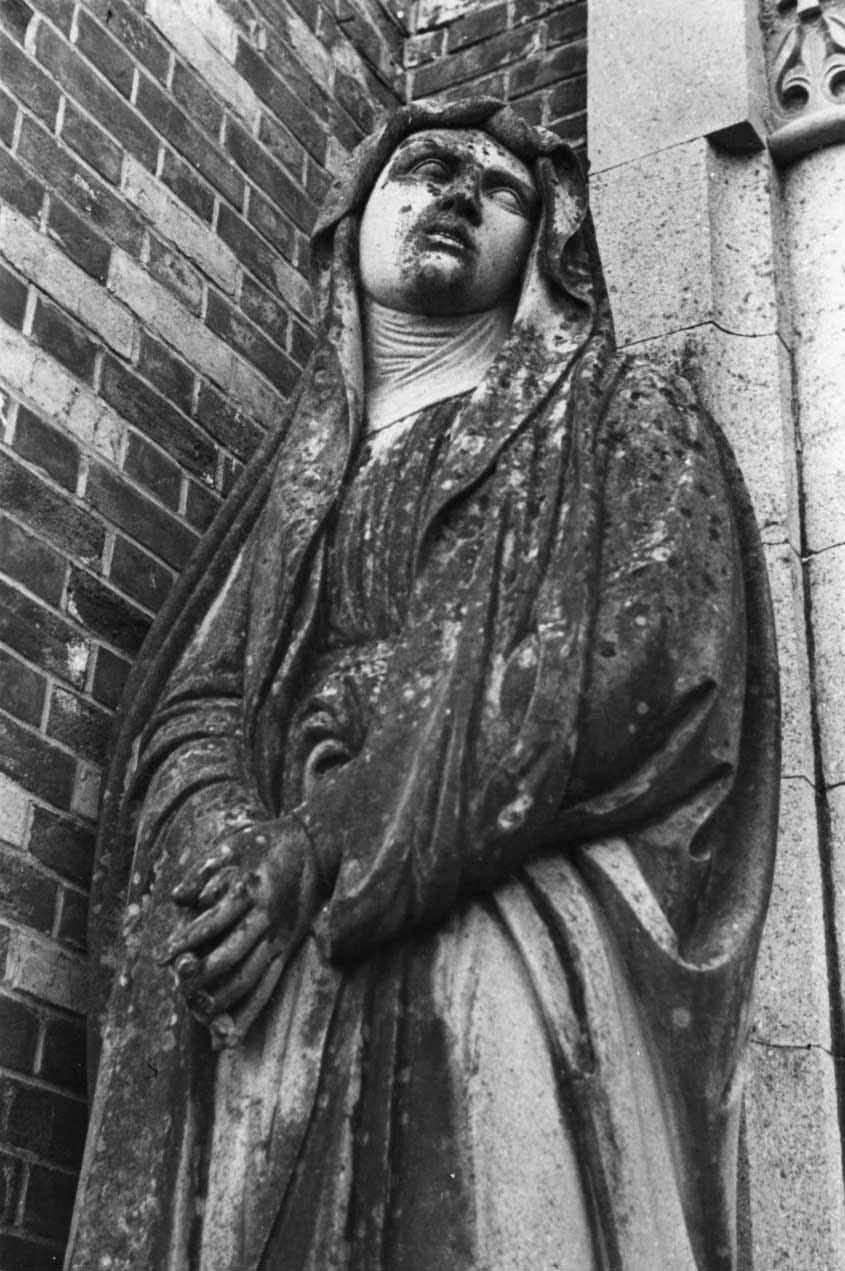

“Mary in Grief” - Urakami Cathedral

Less than a second after the detonation, the northern part of Nagasaki was destroyed and 35,000 people were incinerated, including 6,200 out of the 7,500 employees of the Mitsubishi Munitions plant, and 24,000 others employed in other war plants and factories nearby, as well as 150 Japanese soldiers, one of whom had his skull melted into the top of his helmet as his final remains. A total 96,000 people had died from the bombing and radiation as of a year later.

An American who visits Hiroshima will to this day be made to feel uncomfortable by the citizenry and how they choose to remember the event. The situation in Nagasaki is the exact opposite. After the war, the citizens of Nagasaki determined to find a way to insure such a catastrophe never happened again. They concluded that the only way this could happen was to spread international peace and brotherhood. Nagasaki dedicated itself to that cause. Unlike many cities where the populace has no idea of any “higher purpose” the city might be dedicated to, the people of Nagasaki not only know this, they practice it.

Remains of a Child - this photograph was not allowed to be published until 1962

My ship visited Nagasaki 19 years after the attack. As we came in to the pier, we saw a large crowd of young Japanese students there waiting for us. At the time, there were large anti-American demonstrations in the country over the security treaty, and we thought this might be connected to that. No. These young people were there to greet us, to offer to take us to a restaurant, to offer us a guided tour of their city. They were there to promote international peace and brotherhood, as the city had decided its residents should do. Nagasaki is the one place where I have ever seen the Christian concept of forgiveness truly put to action.

Please consider supporting That’s Another Fine Mess by becoming a paid subscriber for only $7/month or $70/year.

Comments are for paid subscribers.

What you say about the contrast between the response of Hiroshima and Nagasaki is so true, and evident in the atomic blast museums of each city. Hiroshima stresses the victimhood of the residents and paints the US as using the bomb solely to gain advantage over the USSR to preclude its entry into the war. Nagasaki stresses the sadness of it all and concludes with an exhibit on the progress of efforts to control nuclear arms and a plea for disarmament. Very different experiences.

Excellent story, Tom..... I have always found it interesting that with all the protests and throwing paint at the "Enola Gay", "Bockscar" has been displayed at the National Museum of the US Air Force for some decades with almost no notice at all. And may the citizens of Nagasaki prevail in their quest to bring peace to this little blue marble - we have nowhere else to go.....