OPERATION FORAGER - 11 JUNE 1944

This is the first post describing the Battle of the Philippine Sea. The full account is part of the 1944 special posts for Paid Subscribers. This post is offered today for all readers, to give free subscribers who might be interested the opportunity to upgrade to paid to get the entire series.

The loss of the Gilberts in November 1943 and Marshalls in January 1944, with the destruction of Truk as a major Pacific base in February 1944, led to profound changes in the leadership of the Imperial Navy and their plans to oppose further American offensives in the western Pacific. This would lead directly to the Battle of the Philippine Sea, the largest naval battle in history to that time. The change was officially noted when Admiral Soemu Toyoda was appointed Commander in Chief of the Imperial Navy.

Following the Battle of Santa Cruz in October 1942, the Combined Fleet had been reorganized, with the Second Fleet composed of the battleships and cruisers under the command of Vice Admiral Nobutake Kondo, who was replaced in August 1943 by Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita. The Second Fleet was subordinate to the Third Fleet, composed of the nine aircraft carriers in three carrier divisions; Second Fleet was subordinate to and considered the screening force of Third Fleet. Until May 1944, Third Fleet was commanded by Vice Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa, who had replaced Pearl Harbor and Midway commandeer Admiral Chuichi Nagumo when he was removed after the Battle of Santa Cruz.

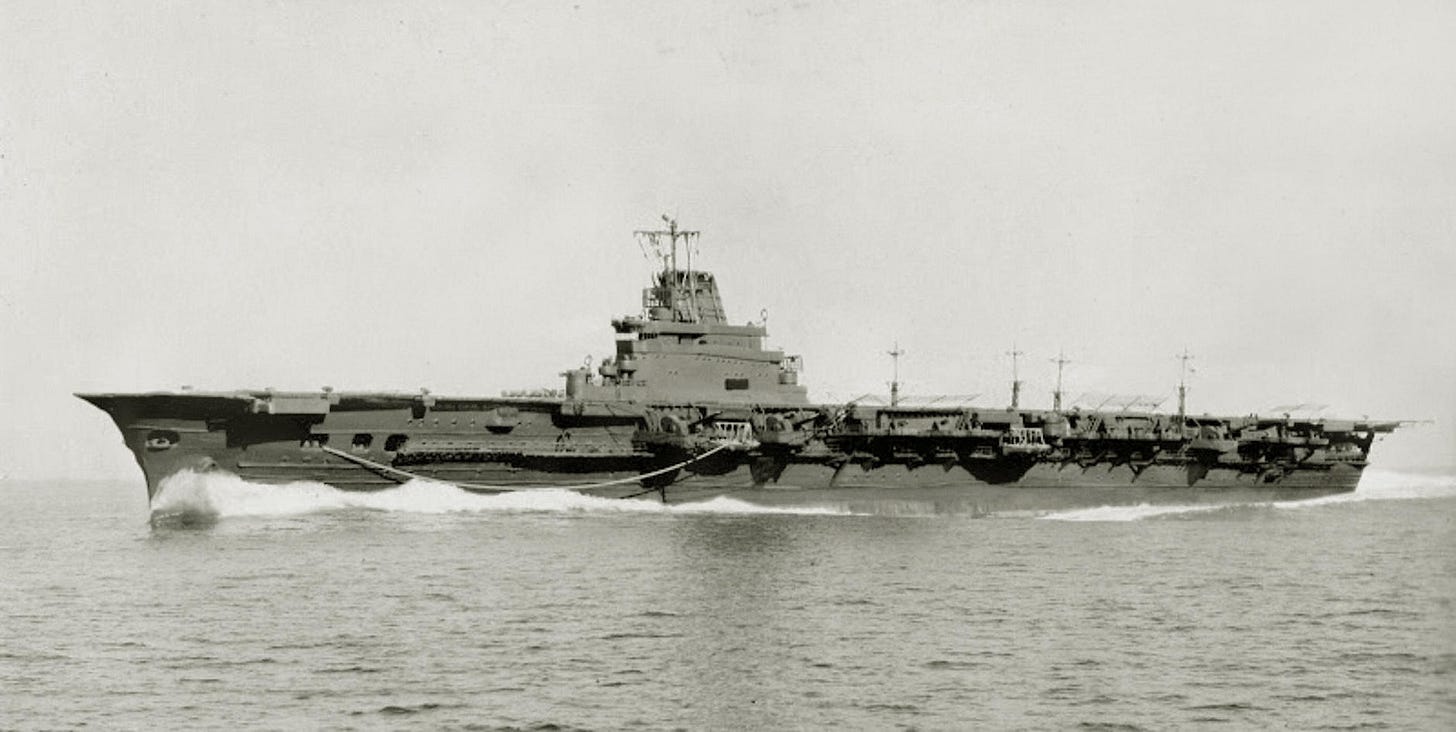

In April 1944, the Navy reorganized the Combined Fleet as the First Mobile Fleet (Dai Ichi Kido-Kantai), composed of Second and Third fleets. Ozawa was moved up to command the Mobile Fleet, retaining command of Third Fleet with his flag aboard the brand new carrier Taihô, an improved Shôkaku-class ship with the first armored flight deck on any Japanese carrier, which had only joined the fleet in February. This reorganization finally placed the carriers at the nucleus of the battle fleet so that for the first time in the history of the Imperial Navy, a carrier admiral controlled the battleships.

Japanese carrier “Taiho”

The Mobile Fleet faced two problems. First, the aviators assigned to the aircraft carriers were incapable of performing as carrier aviators, due to the low level of training. Second was that the fleet was forced to base itself near its fuel supplies in Borneo and Sumatra. Throughout the spring of 1944, the Mobile fleet moved between anchorages in Singapore, Borneo, and the southern Philippines base at Tawi-Tawi in the Sulu Sea. There was a need to keep the carriers near land-based airfields where the under-trained fliers might have the opportunity of further training before going aboard ship. There was an additional problem of the increasing capability of the American submarines, which were now finally equipped with a reliable torpedo, and were using this new capability to attack Japanese warships when found.

Of the nine Japanese aircraft carriers, only Shôkaku, Zuikaku and Taihô were competitive with their American components. Junyô and Hiyô, the next two largest carriers, had been converted from passenger ship hulls in 1942 and were only capable of a top speed of 24 knots. Only the first three were fully capable of operating the new D4Y3 Suisei (Judy) dive bomber and B6N2 Tenzan (Jill), both of which required a wind over the deck to launch that was more than Junyô and Hiyô could manage unless they were heading into a strong wind. The remaining four light carriers - Ryûhô, Chitose, Chiyoda, and Zuihô - were smaller and operated the obsolete D3Y Val dive bomber and B5N2 Kate torpedo bomber.

The new bombers were more difficult to fly. Due to the low training level for their pilots - who had trouble flying these from land bases and had no gunnery or navigation training, forcing them to follow experienced leaders to attack a target. In late March 1944 Zuikaku and Shôkaku moved from to the Lingga Roads off Sumatra which was spacious enough to allow the carriers to conduct flight operations while the narrow entrance protected them from American submarines. Moving to carrier decks resulted in a fearsome rise in losses. Many pilots fell into the ocean turning to final approach due to failure to maintain speed. Many planes failed to hook an arresting wire and careened on into the parked aircraft ahead. Training was ended within a week due to heavy losses and the carriers returned to Singapore where the fliers underwent further land-based training; significantly, they would receive no further training aboard the carriers.

Carriers of Task Force 58

The possibility of the expected fleet battle occuring in the vicinity of the Marianas was not addressed until mid-May. The strategy was for the Mobile Fleet to lure the Americans to them, depending on land-based air units to damage the enemy before the battle. The plan called for Ozawa’s carriers to use the greater range of their aircraft to attack the American carriers while remaining out of range of an American counter-strike, with the poorly-trained carrier pilots landing on Guam to be refueled and rearmed for continued attacks against the Americans from the land bases. The First Air Fleet on Guam was reinforced in late May, with an assigned total of 1,750 aircraft; however, due to a shortage of maintenance personnel, scarcity of ammunition, spare parts, and fuel, First Air Fleet would only have some 435 aircraft available when the invasion came.

Japanese Naval intelligence estimated on 9 May that the Americans would sail with sixteen battleships, eight of which would be new, with eight large fleet carriers, ten light carriers and twenty escort carriers, which was a remarkably accurate assessment.

On 27 May, Japanese plans were thrown into disarray by the American invasion of Biak Island, north of New Guinea. Admiral Toyoda saw this as the American attack he must oppose and prepared to send the fleet to sea. Before Ozawa’s fleet could depart Tawi Tawi, a reconnaissance flight found Task Force 58 in the Majuro anchorage. The Japanese were at a loss: was this fleet to support the invasion that had just happened, or to participate in the expected Marianas invasion? Most Japanese staff officers thought it impossible that the Americans could mount what was seen as two major invasions simultaneously, an indication of how little they understood the nature of their enemy.

Carriers of Task Force 58

The proof that the United States was now the pre-eminent power on the planet was demonstrated when, on the same day that the Allies invaded Normandy, the Fifth Fleet - the largest battle fleet in history - sortied from the Majuro anchorage, headed north to the Marianas. The seven heavy and eight light carriers of Task Force 58 supported 535 ships of Task Force 51, the Joint Expeditionary Force, and 127,000 assault troops of the Second, Third, and Fourth Marine Divisions and the Army 27th Division. More than 300,000 men manned the fleet. That the United States could simultaneously launch two such colossal assaults against separate enemies thousands of miles apart was the clearest demonstration of American globe-girdling military-industrial power after only two and a half years of war.

On 11 June 1944, the Fifth Fleet was 200 miles south-southeast of the Marianas. That morning, two Japanese snoopers were shot down by the combat air patrols.

Both sides now knew the battle was imminent.

This is part of a special series this year commemorating 1944 - the year Amnerica liberated the world - for Paid Subscribers. It’s easy and cheap to join - only $7/month or $70/year, saving $14.

Comments are for paid subscribers.

How badly the Japanese underestimated the U.S. potential. At least Hitler knew it would be trouble if we came into the conflict. Your level of detail is incredible.

Thank you, Tom. How exciting to hear about the Asian Pacific theater of war, Battles of which I knew little. growing up. We were fixated on the European theater, just dimly aware that the war was going on 180 degrees away.