In the summer of 1942, on his 21st birthday, Alfred Theodore Graham, Jr., a small-town newspaper reporter from Jacksonville, New York, enlisted in the U.S. Navy. After training as an aerial gunner and radioman, he was assigned to Bombing Squadron 15, where he served aboard the aircraft carrier USS Essex, departing Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on May 3, 1944, for combat duty in the Pacific.

During the following six months and a week, in between missions in dive bombers battling the Japanese from Wake Island across the Pacific to the Philippines, “Otto” Graham wrote letters, diary entries, small memories of events for a planned postwar book, and columns for the ship’s newspaper, commenting on virtually everything, until exactly 11:00 A.M. on the morning of November 11, 1944 - Armistice Day - when his dive bomber was shot down and he was killed in a sea battle with the Japanese Navy in the Philippines, three days before his Air Group was due to be relieved and return home. On Page 1 of his diary, he wrote:

“Man, it seems, is conceived, born unto the world, lives his life, then leaves the world. But man born unto a world war generation may live but only a part of that life, not realizing even the lesser of his dreams. I am of that age and thinking perhaps some chronicler may some day wonder what some of this great group thought, dreamed, cherished and felt. From the war many will live, of course, but they, in their busy life, may take no time to write their thoughts.”

(I’ve always believed since I first read that, that Ted wrote that across time and space to me.)

Recalled to the Philippines after being sent back to Ulithi for relief and return home, Air Group 15 re-entered combat on November 5, 1944. On November 11, they flew their next to last day of combat and suffered their worst losses of the war.

SB2C-3 Helldiver of Air Group 15

Even after their defeat in the Battles of Leyte Gulf, the Japanese were determined to defend their position in the Philippines. While there had not been many Japanese Army troops on Leyte when the invasion happened, the Japanese Navy began funneling troops from Luzon, putting them ashore in Ormoc Bay on Leyte's western side. The nearby Bacolod air complex became the main base for the Japanese aerial defense and “special attack” (Kamikaze) operations. Halsey planned a major sweep.

On the morning of November 11, Armistice Day, a convoy of four large troop transports and two smaller ones supported by five destroyers was spotted by Essex search missions, bound for Ormoc Bay on the west side of Leyte Island.

The Japanese had managed to land an entire division of the Kwantung Army from Manchuria on Leyte by November 1 in operations that began on October 27. Several later convoys after that were sunk. The convoy spotted now was bigger and closer than any of the others had gotten; it carried most of a second division of Kwantung Army troops. At 0310 hours, off Asbate Island, the Japanese had been unsuccessfully attacked by PT boats. It was estimated the ships would anchor in Ormoc Bay and begin off-loading troops at noon.

CDR David McCampbell, Air Group 15 commander and Navy Ace of Aces

At 0830 hours, Air Group 15 commander David McCampbell led the biggest strike the task group had yet launched to stop the Japanese reinforcements. They reached the convoy at 1030 hours as it rounded Apale Point into Ormoc Bay and was in sight of its anchorage. The ships carried 6,000 troops, plus a three month supply of food and ammunition. The convoy increased speed and scattered as the escorting destroyers began laying a smoke screen.

Twelve Hellcats led by Fighting-15 commander Jim Rigg dove on the ships and strafed as 20 of Bombing 15's Helldivers set up for their attack. Bombing-15 commander Jim Mini assigned targets as the first division dove on the leading transport. Three hits stopped the ship dead in the water. The second division diverted to the next ships and got four hits on the second ship and three on the third but the anti-aircraft fire was devastating.

Lt.(j.g.) John Foote's Helldiver caught fire in the bomb bay just after he dropped his bombs. He pulled out and others saw him seem to gain altitude for a few seconds before nosing over and going straight in. Just before the crash, his gunner, ARM2c Norm Schmidt, was seen to jump from the burning bomber but his parachute failed to deploy. The Helldiver hit the water and exploded.

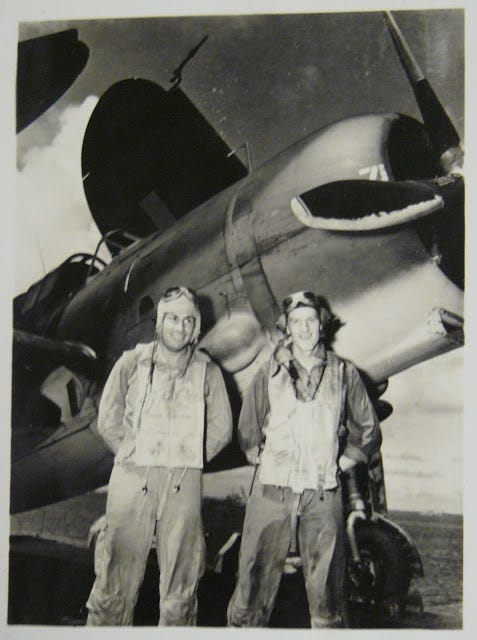

Ensign John Avery (l) and Ted Graham (r)

Two airplanes back from Foote and Schmidt, Ensign John Avery and gunner Ted Graham rolled in and set up on the third cargo ship. Avery dropped his bombs and they were observed as hits. The Helldiver was hit in the engine as it started its climb after pulling out low over the water. The bomber fell off on one wing that caught a wave then it cartwheeled across the water between the ships as it went inverted before tucking and going straight in, disappearing in a geyser of spray. The gunner who had so carefully chronicled the lives and actions of his fellow squadron mates was likely killed instantly. The time was exactly 1100, 11 November.

As if these losses weren't enough, the plane right behind Avery, flown by Ensign Mel Livesay and his gunner ARM2c Chuck Swihart, was struck by AA fire so fierce the left wing was blown off, tearing the Helldiver apart in a violent spiral until the pieces hit the water.

Behind them, Lt.(j.g.) David Hall and his gunner ARM3c Oscar Adams were also hit. Hall was able to keep the Helldiver level and made a successful water landing very near the Japanese ships. The two men exited the sinking bomber and got into their life raft. Later that afternoon they were picked up by an OS2U Kingfisher and returned to the Essex.

“Beanbag Barney” Barnitz felt his SB2C take hits behind and below the cockpit which hit his gunner, ARM2c Neal Steinkemeyer, in his hand and legs. The gunner's wounds and loss of blood were so serious he needed immediate attention; deciding Steinkemeyer wouldn't last till they returned to the Essex, Barnitz headed for Tacloban Airstrip on Leyte. He landed and Steinkemeyer was taken to the base hospital run by the Army. Assured of his gunner's care, Barnitz fired up, taxied out and headed back to the Essex even though several of his flight instruments were shot out.

Lt. (jg) Bob Brice and gunner ARM2c Lou Penza were just behind Barnitz when they were hit and suffered damage to the left wing and fuselage. Brice was able to keep the Helldiver in the air and make it back to the fleet, where he found the landing gear wouldn't come down. He made a successful water landing in the wake of a plane guard destroyer; the two got out before their plane sank and were picked up.

The attack by the Helldivers distracted the Japanese gunners from the incoming Avengers. The 18 Avengers led by Torpedo-15 commander VeeGee Lambert were armed with bombs and rockets. With the first transport sinking, the torpedo bombers attacked the other three large ships, securing hits on the second and third and near-missing one of the smaller transports.

The Japanese convoy was stopped; the cargo ship that sank carried all of the division's ammunition. The Japanese troops that got ashore had few weapons and no ammunition or food. It was a victory paid for by the heaviest losses on a single sortie that Bombing-15 experienced in its whole tour.

When the battered Helldivers got back to the Essex and the gunners realized that the three most popular men in the unit - Norm Schmidt, Ted Graham, and Chuck Swihart - had been lost, it caused a crisis. No one remembered who acted first, but several of the gunners announced they would not fly again in these conditions, that they had done their job and more and they shouldn't still be here. As the men cloistered together on the flight deck, others said they too were refusing more missions. In a moment, all the gunners had joined in. It was the worst crisis of the tour.

Jim Mini went to Dave McCampbell and informed him of the “rebellion.” This was serious. According to “Rocks and Shoals,” as the Navy Regulations were then called, what the men had done amounted to mutiny in wartime in the face of the enemy. The rule book was clear: this was a “hanging offense.” It was in this moment that McCampbell most clearly demonstrated his leadership. He could not go face the men himself in attempt to resolve things, which would thereby make the incident “official.” He and Mini conferred for several minutes about what to do.

Back on the flight deck, the gunners clustered together while the pilots stood aside. After what seemed a very long time, Minireturned and told them McCampbell agreed with them. They would not have to fly any more missions, but would lose their flight papers, which meant the gunners would become part of the ship's company and lose their flight pay. While there was a consequence in the loss of pay and personal status, it was far less than the general courts martial that could have been ordered on the spot.

Then Mini announced that the squadron would continue to make missions with the back seats empty. The gunners looked at each other and then at the pilots, the men they had flown and fought with for the last six months. After a long tense moment, those who had originally stated their decision not to fly announced they took that back. Exhaustion and anger and loss had nearly won the day but the rebellion was over and was never mentioned again.

That night, ARM1c Paul Sheehan, Graham's best friend still alive, opened the diary and wrote the final entry, unable to follow his most famous rule about flying combat: “Never get to like a guy so well you can't see him die.”

“11 November, Armistice Day 1944

Jap reinforcements attempt to land on Leyte and imperil MacArthur's men. 2 DD's, 2 DE's, 4 AK's. At least 20,000 Japs aboard AK's. Task force launched tremendous strike, 20 bombers from Essex. Invasion fleet annihilated!

Otto Graham failed to return from this flight. He was shot down while diving through enemy ack–ack. Two other of our bombers are missing.

Today a great blow was struck by the Navy in defending the Army, but it was truly a sad day for VB-15. We will miss you, Otto Graham, but never forget you.

Aircrewmen of VB-15.”

Sheehan himself would die the next day on the group's final mission against shipping in Manila Bay.

Please consider becoming a paid subscriber - it really helps.

Comments are for paid subscribers.

Beautifully done.

Another tale:

Melvin Shulman was the youngest of three children and the only one to survive his teenage years. When he turned 18, he could have stayed home on hardship, but he was determined to fight the Nazis. He dreamed of being a Navy pilot, went to the recruiting office, and made a discovery when they gave him the color chart he had to be able to read: He was color-blind.

Connections matter. He had a cousin in the Coast Guard who had friends in the Navy and got him a copy of the chart. Melvin memorized what the colors were supposed to be and went back. That morning, they had changed the chart. He enlisted in the Army.

The day came when the doorbell rang at the home of his parents. His father answered the door. A man in uniform stood there and didn't have to say anything. His mother didn't say anything, either. She simply picked up a chair and walked over to her china cabinet. Jews keep two sets of dishes, one for daily use, the other for important holidays. She climbed on the chair, reached up and just dropped each of the religious dishes, smashing them one by one.

Another cousin was a policeman. When the casket came, he went to the funeral parlor and said he wanted to see the body. It was parts.

The policeman had a daughter whose first memory was of having the chicken pox when she was about three, and Melvin coming into her room to say goodbye as he went off to war. She resolved to name a child for Melvin but had a problem: She hated the name Melvin.

She named him Michael.

Here's to our veterans.

History comes alive through your words. I’m grateful.