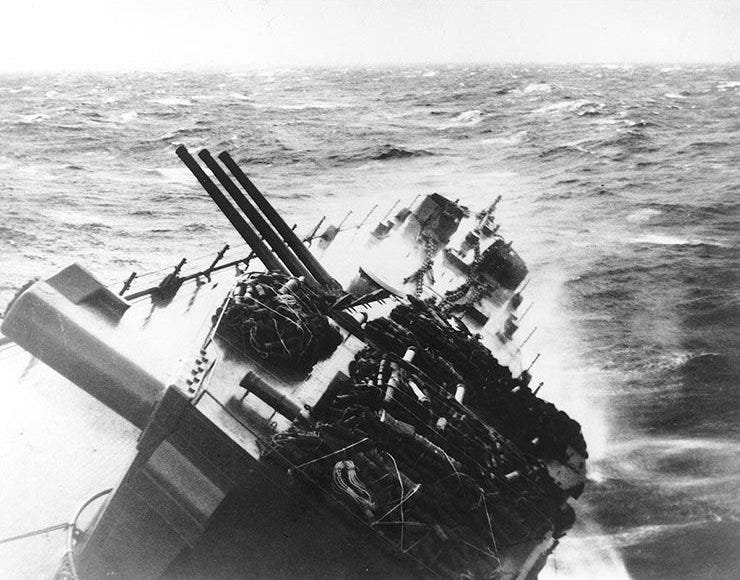

USS Langley (CVL-27 rolls 37 degrees starboard in the storm

Following the three days of strikes in support of the Mindoro invasion, Admiral Halsey ordered the Third Fleet to head east into the open Pacific to rendezvous with the Ulithi fueling group to refuel and transfer aircraft from the five CVEs carrying replacements to the seven fleet carriers and six light carriers of Task Force 38, as well as the eight battleships, 15 heavy and light cruisers, and 50 destroyers which comprised the Third Fleet. That day, the aerologists received warnings of a new typhoon, code-named “Cobra.” Seas became increasingly heavy as the typhoon approached, but Halsey wanted to finish fueling because many of the destroyers were nearly out of fuel. Because they were due to take on fuel, several of the “little boys” did not take on sea water to maintain stability, since it would only have to be pumped overboard again before they could receive the precious fuel oil.

Unfortunately, Commander George F. Kosco, Halsey’s meteorologist did not have sufficient information on the typhoon and its likely track. Early on the morning of 17 December, Kosco advised Halsey that the storm was well to the east and likely to turn north. Halsey believed it would be possible for the fleet to remain together and finish fueling. In the increasingly heavy seas, fueling operations proceeded slowly as tow lines snapped and fueling hoses parted; several collisions were narrowly avoided. Halsey had promised General MacArthur that Third Fleet would return to combat with Philippines strikes on 19 December, and was reluctant to halt fueling. However, sea conditions were such that by mid-day, with the ships of the fleet floundering in mountainous seas and gale-force winds, the admiral concluded that further attempts were only courting disaster and ordered operations stopped.

USS Cimarron attempts to refuel USS Enterprise

Unfortunately, meteorologist Kosco again misread the storm’s projected course as being to the northwest and recommended the fleet steam southwest. Halsey gave the order at dusk for the ships to turn to the new location. Unfortunately, Kosco was wrong, with the result that the Third Fleet was steaming directly toward the heart of an intensifying typhoon.

In spite of the warning signs of worsening conditions as the night became even darker, the fleet remained in formation. With radio antennas broken off, and the weather inhibiting what radio communication was possible, ships remained in their stations with captains unwilling to risk their career to violate the order to maintain formation, despite the danger to their ship.

By midnight, it was obvious the fleet could not reach the new rendezvous; Admiral Halsey ordered the fleet to turn northwest. As it turned out, this put the Third Fleet even more squarely into the typhoon’s path. Over the rest of the night, the wild storm only increased in power.

Aboard the light carrier USS Monterey (CVL-26), Lieutenant Gerald R. Ford, a 31-year old reservist and lawyer from Grand Rapids, Michigan, recently promoted to assistant navigator after serving as gunnery officer in charge of the fantail 40mm mounts, was in the wheelhouse as Officer of the Deck on the mid watch (0000-0400 hours) in the early hours of 18 December. During these hours, the wind built to over 60 knots, while gusts were recorded at 100 knots with lashing rain. The sea became increasingly wild, with waves cresting at 40 to 70 feet before cascading over the bow and crashing into the wheelhouse as they washed on down the flight deck; at times it was impossible to see outside. In 18 months aboard Monterey, Ford had never seen such a storm. As breakers crashed overhead, the men in the wheelhouse could barely hear the sounds of distress through the howling gale — the deep blasts of battleships and cruisers, and the shrill whoops of destroyers. Monterey was a carrier built on a cruiser hull and thus top-heavy in her design. She rolled like a destroyer in the heavy sea.

USS Monterey’s burned-out hangar deck

Following his relief at 0400 hours, Ford made his way below to officer’s country and strapped himself into his bunk. He had only pulled the blanket over him when the klaxon call of General Quarters reverberated through the ship. When he crawled out of his bunk, Ford thought he smelled smoke wafting through the passageways. His battle station was General Quarters Officer of the Deck. He raced through a rolling companionway dimly lit by red battle lanterns to reach the skipper’s ladder outside that led to the wheelhouse, and began to climb. As he hung on the ladder and reached the flight deck, a 70-foot wave broke over the ship and Monterey violently rolled 25 degrees to port. Ford was knocked flat on his back and slammed across the flight deck. Moments from going overboard, he managed to slow his slide and twist to his side so he could fall onto the catwalk where he grabbed hold of a stanchion. He got to his knees and started back up the ladder. This time he made it.

While Ford fought for his life, aircraft chained down on the hangar deck broke loose when the ship rolled 30 degrees port, then 30 degrees starboard. They slammed against each other as they bounced off the bulkheads. The collisions ignited full gas tanks and soon the hangar deck was a sea of flame. Because of a quirk in the ship’s design, the flames were sucked into the air intakes for the lower decks and fires broke out below the hangar deck.

Damaged TBM Avenger on USS Anzio

Monterey was ablaze from stem to stern when Ford arrived in the wheelhouse. Captain Stuart Ingersoll had received orders from Admiral Halsey to abandon ship, but was determined to save the carrier if he could. He ordered Ford to go below and assess the raging fire. The ship had gone dead in the water when smoke was sucked into the engineering compartments. Damage control parties slipped and fell on the deck as Monterey wallowed in the giant waves while they desperately played fire hoses over the blaze. Ford did so and returned to the wheelhouse to report he believed there was a fighting chance to save the ship. He then took his position as General Quarters OOD while Captain Ingersoll fought to save his ship.

Below in the hangar, sailors donned breathing masks and entered the burning compartment. Hose handlers slipped and fell, sliding across the deck as the ship rolled in the wild sea. The first order of business was to carry out the dead and injured.

The fight was exhausting over the next several hours, but by dawn the men emerged from the dark hellhole. The fire was out. Three men had died in the flames with 40 injured. Monterey would require long-term repair at the Bremerton Navy Yard, where she arrived the first week of January 1945. She returned to the combat zone at the end of March and participated in the Okinawa campaign.

USS Cowpens in the storm

Monterey wasn’t the only carrier that barely escaped loss. USS Cowpens (CVL-25 had her hangar door torn open. The main radar, a 20mm gun sponson, the whaleboat, and jeeps, tractors, and the crane were lost overboard while eight aircraft were destroyed in the hangar deck and one sailor was lost at sea. USS Langley (CVL-27) suffered damage to her gun sponsons while several aircraft were damaged in the hangar deck. USS Cabot (CVL-28) was damaged by the storm sufficiently to need a week of repair at Ulithi. Aboard USS San Jacinto (CVL-30), planes on the hangar deck were tossed about and destroyed air intakes, vent ducts and the sprinkling system, which caused widespread flooding. All of these incidents were due to the top-heavy design of the light carriers.

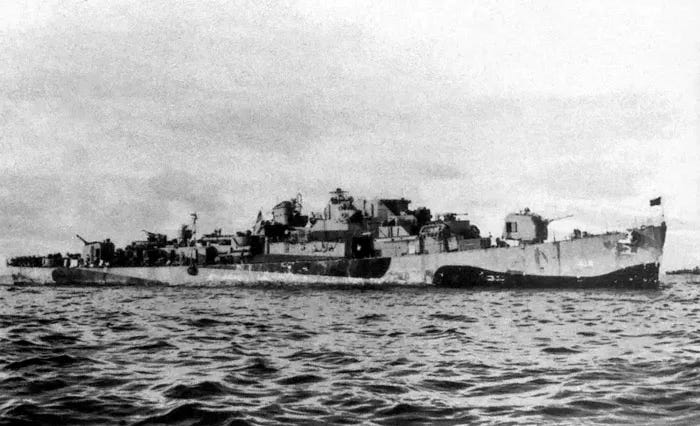

Aircrat damage on USS Nehenta Bay CVE-74

The escort carriers operating with the Ulithi refueling group also suffered damage in the typhoon. USS Anzio (CVE-57) suffered damage that required major repair before she could rejoin the fleet in time for Iwo Jima. USS Nehenta Bay (CVE-74), which was assigned as an anti-submarine escort for the fleet oilers along with Anzio, was damaged by high waves that swept the ship. The CVEs assigned to carry replacement aircraft for Task Force 38, were also damaged. The hangar deck crane broke loose on USS Altamaha (CVE-18)and crashed into aircraft tied down there, causing a fire that was difficult to put out due to the fact the crane also broke the fire mains. USS Cape Esperance (CVE-88) suffered a flight deck fire that required major repair at Pearl Harbor while USS Kwajalein (CVE-98) lost steering control until power could be restored when the electrical system shorted out from water. 146 aircraft aboard the CVLs and CVEs were lost in the storm.

Battle4ship USS New Jersey in storm with USS Ticonderoga

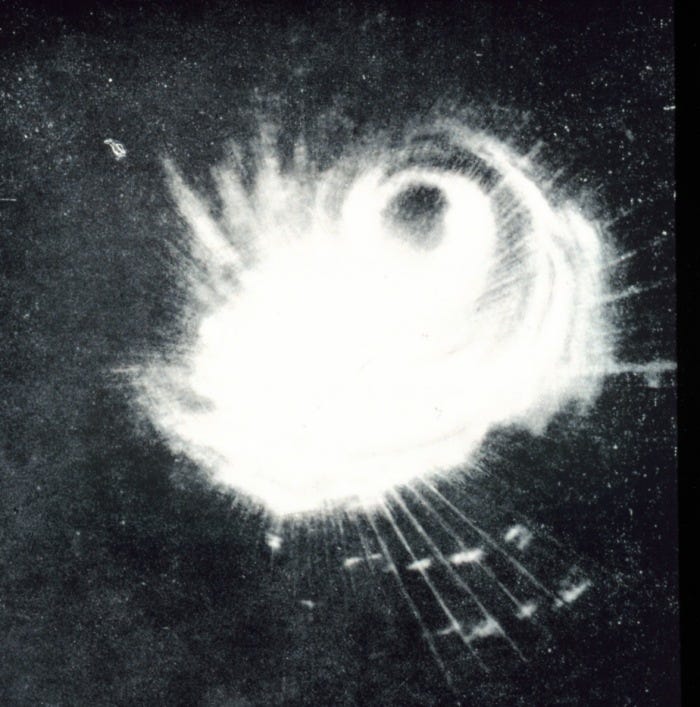

At 0500 hours on 18 December, Halsey surrendered to the inevitable and all ships were ordered to make best speed to the south. By this point, the ships of the Third Fleet were scattered across 2,500 square miles of ocean. Some ships were in better conditions than others. Hancock recorded only scattered showers in the morning, while USS Wasp (CV-18) found mid-morning seas that were recorded as “mountainous.” At one point, she passed so close to the eye of the storm that it painted on the surface search radar screen; an image taken of the screen was likely the first time any human had seen a typhoon’s cyclonic heart.

Radar image of Typhoon Cobra

While the carriers ran into trouble, it was nothing like what the “small boys” - the destoyers - dealt with. With 100 knot winds, 70-foot seas and torrential rain, the little ships had great difficulty, especially since there were no orders given allowing them to maneuver as sea conditions warranted for safety. (This part of the struggle against the storm was dramatized in both the novel and the motion picture of “The Caine Mutiny,” where the event that leads to the “mutiny” is Captain Queeg’s refusal to alter course into the wind, as he blindly follows his last orders. Author Herman Wouk actually experienced Typhoon Cobra and was writing from memory.)

Light cruiser USS Santa Fe (CL-60) rolls 35 degrees starboard

For three destroyers the event became fatal.

USS Spence (DD-517), a Fletcher-class destroyer that was a veteran of Commodore Arleigh A. “31-Knot” Burke’s famed DesRon-31 “Little Beavers” destroyer division in the Solomons, had pumped the salt water ballast from her tanks on 17 December in preparation for fueling. Unable to refuel when the hoses broke repeatedly, Spence was drastically unstable. As she wallowed in canyon-like troughs in the early morning light of 18 December, she took a 72 degree roll to port, which caused loss of all electrical power due to water shorting out the system. All lights went out and the pumps stopped while the rudder jammed hard right. After another deep roll to starboard at about 1045 hours, Spence rolled over and sank. Only 24 crew members eventually survived, including steward David Moore, an African American who survived two days in a raft in the vicious seas and managed to save two others.

USS Hull (DD-350) and Monaghan (DD-354) were older pre-war Farragut-class destroyers that had been refitted with nearly 500 tons of additional topside weight in the form of additional anti-aircraft batteries, radar, and other equipment, which made them top-heavy even in normal operating conditions. Operating as escorts for the fueling group, both ships had sufficient fuel to provide stability, but their dangerous top-heaviness proved their undoing. When their inexperienced captains continued to follow orders to maintain formation, even when this meant taking the sea broadside. By mid-morning on 18 December, both eventually rolled so violently in the troughs that they went so far over that sea water flooded down their stacks and disabled their engines. Without power, they lost all control and were unable to turn into the wind. At the mercy of the wind and sea, both capsized and sank, with Hull sinking at 1100 hours and Monaghan at 1130 when the last of her generators gave out and the ship lost power with her rudder jammed. One survivor recalled that Monaghan rolled violently seven times before she broached and was carried to the crest of a wave where she fell over and was buried in the crashing waves.

USS Maddox in the typhoon

The other two destroyers that were nearly empty of fuel and unstable were USS Hickox (DD-673) and Maddox (DD-731), which were both able to pump seawater into their empty fuel tanks which gave them sufficient stability to ride out the storm with only minor damage. LCDR J.H. Wesson, commander of Hickox, saved his ship by disobeying orders to maintain course and heaving to in order to face the storm.

By mid-afternoon, the worst had passed and the wind and sea moderated. At sunset, some ships reported seeing the sunset, and by nightfall the winds had dropped below 60 knots. At 1848 hours, Admiral Halsey ordered all ships to post additional lookouts to spot any men washed overboard. At midnight, he received the first reports of loss when USS Tabberer (DE-418) reported she had rescued ten survivors from Hull, including the captain. Badly shaken by the news, Halsey ordered an all-out search. It was clear to that he would not fulfill his promise of air strikes on 19 December. The morning of 19 December dawned clear and placid in the Philippine Sea, but by 21 December the remnants of Typhoon Cobra had settled over northern Luzon and all flight operations in the Philippines were canceled. The Third Fleet took course for Ulithi and repairs.

USS Tabberer damage from the storm

Perhaps the most heroic performance by any ship during the typhoon was that of Tabberer, a small John C. Butler-class destroyer escort that lost her main mast and radio antennas. Though damaged, the ship remained on the scene and recovered 55 of the 93 total sailors who were eventually rescued over the next three days. Tabberer’s captain picked up men found in the sea by bringing the ship to a halt fifty yards upwind of the target and letting the waves and wind carry the ship to the floater. 28 Hull survivors were found on 19 December, with survivors from Spence being found the next day when Tabberer joined up with USS Swearer (DE-186) and Knapp (DD-653). On 21 December, USS Brown (DD-546) found the last 12 survivors of Hull and the six who were the only survivors of Monaghan. Tabberer’s captain, LCDR Henry Lee Plage, was awarded the Legion of Merit for his action, while the entire crew earned the new Naval Unit Commendation, which was presented personally to them by Admiral Halsey. A total of 93 survivors of the three ships were rescued, but over 800 sailors perished.

In addition to the loss of the three destroyers and the damage to the light and escort carriers, the battleship USS Iowa (BB-61) lost one of her OS2U-3 Kingfisher seaplanes and had a propeller shaft bent. The cruisers USS Baltimore (CA-68) and Miami (CL-89)required major repair. Destroyer USS Dewey (DD-349) lost her steering control, and radar when saltwater entered the forward stack and shorted the main electrical switchboard. Destroyers USS Aylwin (DD-355), Buchanan (DD-484), Dyson (DD-572) and Benham (DD-397) and destroyer escorts USS Donaldson (DE-44) and Melvin R. Nawman DE-416) all required major repair.

Destroyer escort USS Waterman (DE-740), fleet oiler USS Nantahala (AO-60), fleet tug USS Jicarilla (ATF-104) and ammunition ship USS Shasta (AE-33) were damaged.

Reviewing the event, Admiral Chester Nimitz wrote that the typhoon’s impact "represented a more crippling blow to the Third Fleet than it might be expected to suffer in anything less than a major action".

A Court of Inquiry was convened At Ulithi, on 26 December, chaired by three admirals, in the wardroom of the destroyer repair ship USS Cascade (AD-16). LCDR James A Marks of Hull, the only surviving captain, was the sole “defendant.” His defense of his actions was that Hull had not been released from station until early on 18 December and that he was following orders. He was exonerated.

The most prominent witness was Admiral Halsey, who testified that solid evidence of a typhoon had not been confirmed until 0100 hours on 18 December. His commitment to resuming strikes on Luzon “was uppermost in our minds until the last minute,” which is why he had continued the attempt to refuel.

On 3 January 1945, the court returned a 200-page, single-spaced report with 157 “Findings, Opinions and Recommendations.” The losses of Hull and Monaghan were attributed to their inexperienced captains, older designs and top-heavy retrofits. LCDR James Andrea, captain of Spence, was posthumously faulted for failure to ballast his tanks and for not removing topside weight. Commander Kosco was admonished for relying too much on remote weather reports rather than the situation at hand. Task Force 38 commander Vice Admiral John S. McCain, Sr., was admonished for turning his carrier groups directly into the typhoon’s track.

In judging the actions of a popular fleet commander, the court’s words regarding Halsey were measured if not equivocal. The carefully-parsed conclusion was that Halsey’s “mistakes, errors and faults,” were “of judgement under stress of war operations,” rather than “offenses.” On 22 January, Admiral Nimitz approved the court’s findings. Nimitz stated for the record that Halsey’s mistakes and errors stemmed from “a commendable desire to meet military commitments,” and no further official action was taken. Nimitz sent his commander what has been called an “exceedingly frank” personal letter that has never been declassified. Halsey’s fighting qualities had been judged essential for the road ahead.

I hope you will consider becoming a paid subscriber to support That’s Another Fine Mess, it really helps!

Comments are for paid subscribers.

Quite a report, TC and so well written I felt the horror of it. 800 lives lost and an experience that probably haunted the survivors for the rest of their lives. Those patriots fought to save the world from dictators who didn’t care about freedom. The cultists who are eagerly supporting an American dictator/psychopath need a good shake.

The Navy passed judgement on Halsey posthumously. Raymond Spruance lent his name to a large class of destroyers (the "Spru-cans") that served for decades and were a notable departure from prior designs. Arleigh Burke was the namesake for the Burke class destroyers, still building an in serve. Halsey got two ships named after him, but not a class. I think the typhoon and leaving Samar undefended was not talked about that much but definitely noticed.