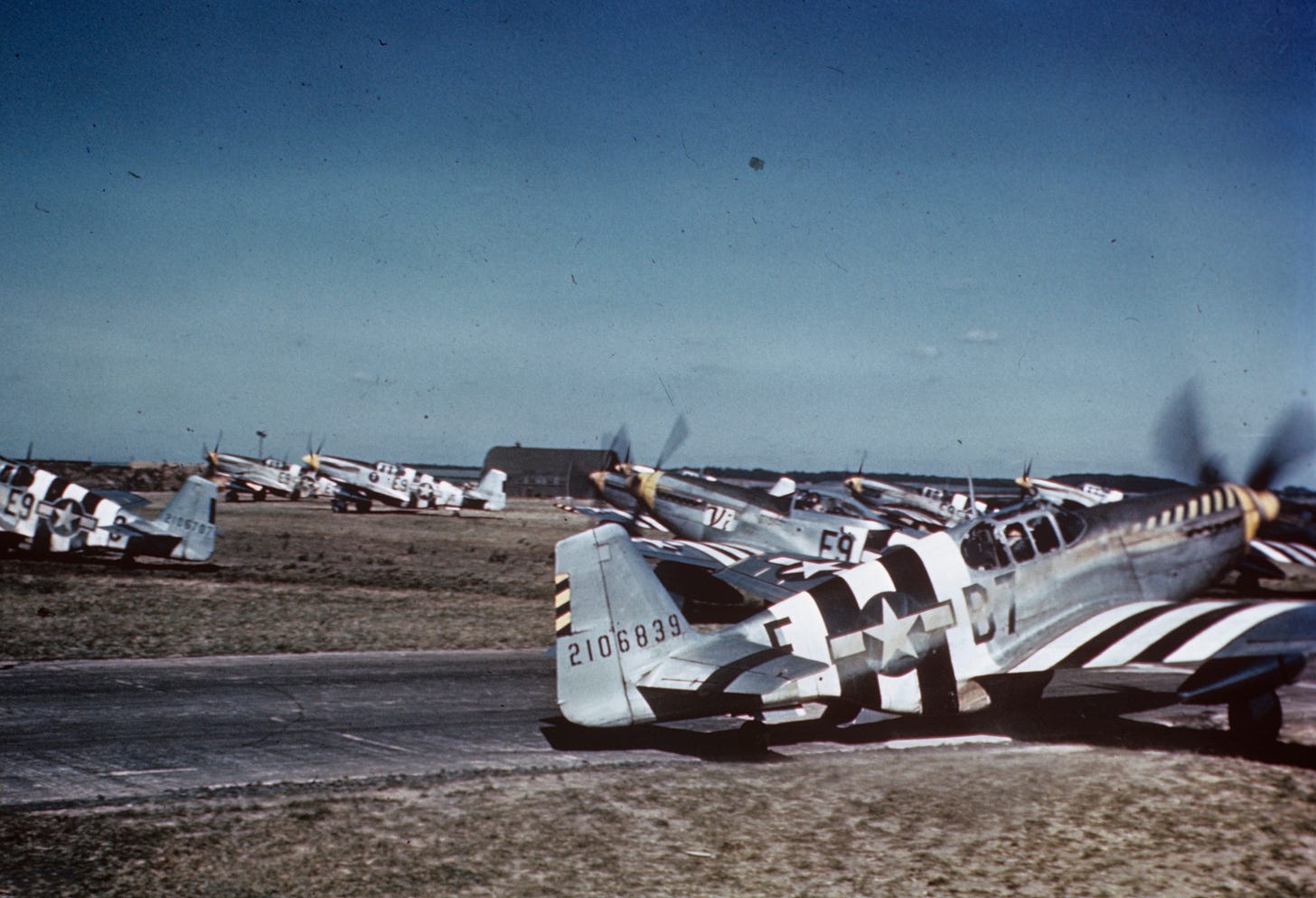

D-DAY REMEMBERED

P-51 Mustangs of the 361st Fighter Group prepare for takeoff on D-Day

With the fighters of IX Tactical Air Command striking every target they could find in Northern France and Belgium, and fighter groups from VIII Fighter Command strafing targets during their returns from every escort mission, while A-20 Havocs and B-26 Marauders of the IX Air Force and the Eighth’s B-17s and B-24s hit every rail target in the region, the German Army in northwestern France was cut off from its supply bases.

The strikes on airfields forced the defending Luftwaffe fighters to pull back deeper into France and Germany. The week before the invasion, the commander of the German Seventh Army, tasked with defending Normandy, called the roads in the army’s area of operations “Jabo Rennstrecki” (fighter-bomber racecourses).

he Luftwaffe had fewer aircraft available on the Channel coast at the end of May 1944 than had been available at the time of the Dieppe Raid in August 1942. JG 2, which had been assigned to the Cherbourg Peninsula since 1941, was closest to the Normandy beaches. I/JG 2 had only recently returned from the fighting at Anzio. The Bf-109-equipped II/JG 2 was at Creil outside Paris, while III/JG 2's Fw-190s were in the process of transferring to Fontenay-le-Comte north of La Rochelle.

With a forecast for stormy weather during the first week in June that seemed to preclude any likelihood of invasion, JG 26 Kommodore Oberst Josef “Pips” Priller felt safe giving some pilots time off. II Gruppe left for Mont de Marsan near Biarritz for a week’s leave on June 1. The other two gruppen were ordered to move inland on June 5, with I Gruppe moving to Reims and III Gruppe to Nancy. Their ground echelons were still on the road when dawn came on June 6.

P-51D-5 Mustang of the Fourth Fighter Group

The Fourth Fighter Group - known in VIII AF Fighter Command as The Debden Eagles for their formation from the RAF Eagle Squadrons, “The Yanks in the RAF” - was based at Debden in East Anglia. Pilot Bob Wehrman remembered “None of us had slept much that night. The sky was filled for hours with the drone of aircraft. I spotted bombers heading toward invasion targets and C-47s carrying what I later learned were the British and American paratroops.”

At Duxford, not far from Debden, 78th Fighter Group ground crewman Warren Kellerstadt recalled: “They didn’t tell us when D-Day was going to be, but the night before we could smell something in the wind. They closed up the base tight and wouldn’t let anyone on or off and right after supper on June 5, they ordered black and white stripes painted around the wings and fuselages of the planes. We armorers were kept busy all night lugging bombs from the dump out to the dispersal area to stack next to the planes. I worked til midnight, then had guard from 0200 hours. All night long the bombers went out, first the RAF, then ours. They all had their navigation lights on because there were so many of them they had to worry about collisions, and the sky looked like a Christmas tree, full of red and green lights.”

0200, June 6, 1944: dawn was already rising with Double Wartime Daylight Savings.

At the former RAF station of Beaulieau Roads, between Southampton and Bournemouth, now home to the 9th Air Force's 365th Fighter Group, known as “the Hell Hawks,” the rumble of 48 Pratt and Whitney R-2800s reverberated across the quiet English countryside.

On the taxiway, the big P-47 Thunderbolts, each resplendent in the black and white identification stripes hurriedly applied with mops and brooms by the ground crews two nights before, S-turned under their heavy loads of two 500-lb bombs on the wing shackles and a 110-gallon drop tank on the centerline mount as they taxied toward the runway in the growing dawn light.

P-47D-11 Thunerbolt of 362nd Fighter Group on D-Day

At the runway, the flagman checked each pair as they moved into position. The engines roared as the pilots advanced their throttles to takeoff power, then started their takeoff roll as they were waved off.

Number eight of the sixteen P-47s of the 388th Fighter Squadron was 2nd Lieutenant Archie Maltbie, who had arrived in the squadron three weeks earlier and for whom this was his first operational mission. Maltbie ran his hands over his wool pants to dry his sweating palms, then pulled on his flying gloves.

The two airplanes ahead moved into position and took off.

The ground crew signaled Maltbie and his element leader to move forward.

Once on the runway, he checked the engine instruments, worked the controls quickly in a last-minute check, and pushed the throttle forward when the checkered flag came down. Halfway down the runway, the Thunderbolt's tail came up, and then he was airborne as the main gear thumped into the wells.

A right turn brought the two Thunderbolts over the Isle of Wight in a matter of moments. They joined the rest of the formation as the fighters circled until all had joined up, then the formation headed east across the English Channel toward the coast of Normandy.

"I'll never forget what it was like that day. There were so many airplanes in the sky that there was a serious risk of collision, and there were so many ships in the Channel it seemed that you could have walked from ship to ship from England to France."

The 78th Fighter Group cranked engines at 0320 hours for their first D-Day mission. Rain poured and visibility was so bad pilot Richard Holly remembered that when Colonel Gray’s first section took off, “He just barely cleared the end of the runway before he was out of sight.” When his flight lined up for magneto check Holly instructed the other three pilots to set their gyros on his and follow him. “It was the only instrument takeoff I made in the war and also the only one I made with water injection all the way because we were so heavy.”

The 78th’s P-47 Thunderbolts found themselves flying in and out of rain showers across the Channel. As they flew through one storm, they encountered a formation of RAF Lancaster heavy bombers and barely avoided disaster. Holly remembered, “I did not see anything on the ground through the clouds, but the red glow below the clouds told us it was Omaha Beach. As it got daylight the red glow went away but we knew from the smoke and haze there was still plenty going on down there.”

A formation of Ninth Air Force B-26 Marauder bombers were caught over Pointe du Hoc just after dawn by 20 JG 2 Fw-190s as the Marauders bombed the clifftop prior to the landing of the Army Rangers tasked with spiking the guns there. The Luftwaffe fighters made one pass and then turned back to their base as masses of Allied fighters appeared overhead. This was the biggest battle fought by the Luftwaffe on D-day.

The assignment for the Hell Hawks that day was to patrol the Cotentin Peninsula, to block any Luftwaffe aircraft that attempted to attack the invading American forces at Omaha and Utah Beaches and attack any enemy ground units spotted.

After an hour, the Thunderbolts were free of their bombs and most of their ammunition.

P-47D “Hairless Joe” of 56th Fighter Group

Returning to base, the pilots told the excited ground crews what they had seen. After a quick meal, they were back in their planes for a second sweep of the beachhead.

The 78th flew three missions over the course of the day. Using both A and B groups, planes were landing and taking off at Duxford all day long. Eight-plane attacks were made on targets inland.

The 83rd Squadron bombed a railroad bridge 40 miles west of Paris, while the 84th Squadron hit the Alencon marshaling yard and blew up a nearby ammunition dump.

Armorer Kellerstadt remembered, “All that day they were dive bombing and strafing everything that moved. When they returned from a mission, we hopped on the planes, rearmed and bombed them, and cleaned as many of the guns as we had time for before they took off again.”

“Pips” Priller learned the invasion was on when he was awakened by the phone in his Lille command post. It was from 5th Jagddivision, ordering him to move his headquarters immediately to Poix, closer to the anticipated invasion site on the Pas de Calais.

“Pips” Priller and his Fw-190A-8 on D-Day

The dawn skies were a leaden grey at 0800 hours when Priller and his longtime wingman, Unteroffizier Heinz Wodarczyk, mounted their Fw-190A-8s and prepared to take off for a reconnaissance of the invasion beaches.

With Wodarczyk sticking close, Priller headed west at an altitude of 100 meters. East of Abbeville, he looked up and saw several large formations of Spitfires flying through the broken cloud base. Near Le Havre, he climbed into the cloud bank hanging at 200 meters and turned northwest. Moments later, the two fighters broke out of the clouds, just south the British invasion beach code-named Sword.

Priller only had a moment to stare out to sea at the largest naval force ever assembled in history. He could see wakes of the inbound invasion barges as they approached the beaches for as far as he could see in the hazy weather.

With a shouted “Good luck!” to Wodarczyk, Priller winged over into a dive as his airspeed indicator climbed above 400 m.p.h. Dropping to an altitude of 50 feet, the two roared toward Sword Beach, where British troops dove for cover while ships offshore opened up with a barrage of anti-aircraft fire so loud those on the ground had trouble hearing Priller and Wodarczyk open fire as they flashed overhead, unscathed by the fleet’s fire.

In a moment, the only appearance by the Luftwaffe over the Normandy beaches on D-Day was over. Priller and Wodarczyk zoomed back into the cloud bank and disappeared, having just flown the best-known mission in the entire history of JG 26, due to its later inclusion in Cornelius Ryan’s book “The Longest Day” and the movie made from it.

Maltbie remembered, "We thought that was it for the day when we got back from the second mission, but all of a sudden there was a call that radar had picked up the Luftwaffe heading toward the beaches, and all the airplanes that had been fueled were scrambled. There were no Germans around by the time we got there."

The 78th Group’s final D-Day mission was flown at 1800 hours. Thirty-two P-47s patrolled the area from Chaillone to Coulonche. Two flights from the 84th strafed a train pulling fuel tank cars that exploded so violently the debris hit the attackers. Wallace Hailey had to abandon WZ-F over the Channel and was quickly rescued by ASR; two other damaged Thunderbolts managed to land safely at the RAF Coastal Command airfield at Ford.

When the Thunderbolts returned to Duxford, night had fallen on England.

That night, after flying two missions during the day, B-17 co-pilot Bert Stiles - later the author of “Serenade To The Big Bird” - wrote in his journal, “The only thing that matters is to win, win in a way so there is never another one.”

June 6, 1944 marked the beginning of the eleven bloodiest months in world history as the battle to defeat fascism began its final act.

Sixty years later, Archie Maltbie told me, "It really was the longest day I can ever remember."

Comments are open for all subscribers.

Thank you, Tom. I remember D-Day very well. We had such high hopes, the naziss would surrender by Christmas. But it didn't happen. Eleven more months. The nazis resorted to sending children (the nazi youth) to fight for them, some as young as me (11 to 12).

And like the first world war, it wasn't the war to end all wars - the military industrial complex were making too much money and were too busy designing more lethal weapons. So we soon had the Korean War, the Vietnam War, the continuing endless wars in the middle east, the Bosnian War, the Iraqi War, The Afghani War, ad now the Russian attack on the Ukraine. For what? to give old men a chance send young men (and women) to their death? to assure the continuing wealth of the ammunition industry? I'm sick of war. The money we waste to kill other human beings could better be spent on education, affordable housing, food production. Guess I'm just in a funk tonight.

It’s almost like you (and us) had a front row seat to the heroes and their battle for our country and the world that day. How ashamed I am of our country today. Every magat likely had someone who died or was maimed in that war. My bros do, but that was a generation back. They likely don’t remember the grief of my aunt who lost her 19-year-old son before DDay. They die, we forget, they die again. Thank you for reminding us of their longest day and why they demand that we remember, for the generations to come