APRIL 18 1942: “OUR TARGET IS TOKYO”

This was supposed to go up yesterday but “life intervened.”

Jimmy Doolittle (l) and Hornet CO Marc Mitscher with the Raiders before takeoff

Over the three months since John Bridgers had arrived at NAS Barber’s Point, he had trained hard to become a dive bomber pilot. He recalled, “Bombing Three provided the Navy a handy place to familiarize a group of newly-hatched replacement scout-bomber pilots with the Douglass SBD Dauntless, which none of us had previously seen, much less flown. The veteran Saratoga pilots resented the idea of having to take us on familiarization flights, sitting in the rear-seats of their planes while being piloted by fellows several years their junior in age and experience. Their headquarters and ready room were in a beach house alongside the airfield, left over from the beachside holiday spot the area had been before it was converted to an air station shortly before hostilities started. In their mind we unnecessarily cluttered their living and work place, and it was frequently suggested that we spend more time outdoors. There were worse places to be than outdoors in Hawaii.”

Saratoga had left a Landing Signal Officer behind, and he trained the “nuggets.” Bridgers recalled that he was given orders to join Bombing Five in late March, pending the return of Yorktown from the South Pacific. However, in early April, “Suddenly I was in a hybrid air group made up of Enterprise and Saratoga pilots, at sea and bound for what none of us knew. We sailed northwest and, in the vicinity of Midway Island, our group was joined with another task group including the USS Hornet (CV-8), an Atlantic fleet carrier which had been transferred to the Pacific. Her flight deck was fully loaded with Army Air Force B-25 medium bombers. As was typical for wartime operations we embarked with sealed orders, operational plans that were unseen by the ship's commander. These were carried in the skipper's safe and not opened until a given time or at a given location out at sea. In this case ours were opened and made known to all hands when we rendezvoused with the Hornet group. We learned that we were going to sail within several hundred miles of Japan. Then the B-25s on Hornet’s deck, under the leadership of Colonel Jimmy Doolittle, an aviator whose exploits all of us knew, would take off from the Hornet, bomb targets in Tokyo, and fly to China. At best, it would be a perilous undertaking.”

Hornet with B-25s enroute

Dick Best, now commander of Bombing Six recalled, “I was floored to see Hornet rendezvous with us with all those Army bombers on her deck. It was obvious to anyone that we were now involved in the most important mission of the war to date. I knew they were going to hit Japan, and I only wished it was we who could do it, but such was impossible.”

The mission Ensign Bridgers and Lieutenant Best found themselves part of had been in planning since early January, a month after the Pearl Harbor attack. On December 21, 1941, President Roosevelt met with the Joint Chiefs of Staff at the White House. At that meeting, he told his military leaders that he believed Japan should be bombed as soon as possible to boost public morale following the Japanese attack.

On January 10, 1942, Captain Francis Low, Assistant Chief of Staff for Anti-Submarine Warfare, submitted a memorandum to Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Ernest J. King, expressing his belief that twin-engine Army bombers could be launched from an aircraft carrier and that they could then strike Japan. The memo was result of research by Captain Donald B. Duncan, King’s air operations officer, to whom Low had first taken his idea; he had concluded such an operation was technically feasible. King passed the Low Memorandum on to General Henry H. “Hap” Arnold,, who called in his new special projects officer, Lt. Colonel James H. “Jimmy” Doolittle, America’s most famous test and race pilot, who had given up his position as a Shell Oil vice-president in charge of aviation fuel development where he had been responsible for the pre-war development of 100-octane aviation fuel that would eventually guarantee American technological superiority in the coming war, to return to military service; Doolittle was ordered to investigate the feasibility of such a proposed mission.

Doolittle and Captain Duncan studied the available USAAF bombers and concluded that the only one that could carry out such a mission was the North American B-25 Mitchell. This was primarily due to its weight and wingspan, which would allow it to take off from the deck of a Yorktown class aircraft carrier. They successfully demonstrated the concept when they flew two B-25Bs off the deck of Hornet (CV-8) in Chesapeake Bay on February 3, 1942.

With the decision made to use the B-25, Lt. Colonel Robert D. Knapp, a man with a lifelong involvement in Army aviation as the 137th Army Aviator, who had met the Wright Brothers at age 10 when they stayed with his family for ten days in 1907, was brought into the project. He had been assigned to organize the new bomb groups equipped with the B-25; by the spring of 1942, Knapp personally knew every B-25 pilot in the USAAF and was intimately aware of their individual abilities. He recommended that Doolittle work with the 17th Bombardment Group (Medium), composed of the 34th, 37th and 95th Bombardment Squadrons and the 89th Reconnaissance Squadron, since the 17th was the first unit to take delivery of the B-25 in September 1941 and they were now the most experienced Mitchell crews in the air force.

Knapp accompanied Doolittle to visit the 17th group, where he told the men of a special “extremely hazardous mission” in which the rewards reflected the hazards. Pilot Ted Lawson, who would later write “Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo,” the definitive first-hand account of the mission, remembered “When Jimmy Doolittle stepped onto that stage to address us, everyone knew this was something we didn’t want to miss.”

Ted Lawson’s crew - Lawson is 2nd from rt

The only hint they got of where they were going came when they landed at Eglin Field, Florida, to meet Navy Lieutenant Henry L. Miller, a naval aviator who instructed them over the next few weeks on how to take off in a fully-loaded B-25 after a takeoff run of only 450 feet, lifting off only slightly above stalling speed. The pilots accurately concluded they were going to hit a target in the Pacific, though they wrongly guessed the Philippines

The B-25s were highly modified. The retractable ventral turret was removed, saving 600 pounds which allowed more fuel to be carried, After the modifications, the total fuel load came to 1,117 gallons: 646 gallons in the wing tanks, 227 gallons in the bomb bay tank, 160 gallons in the collapsible crawlspace tank above the bomb bay, another 160 gallons in the ventral turret space, and ten five gallon cans for refills carried in the rear fuselage. Each bomber would carry four 500-pound bombs, other than Doolittle and the first four, who carried three 500-pound bombs and a 500-pound incendiary to mark the targets. The only defensive armament was the Martin power-operated turret located aft of the wing amidships in the fuselage. Two wooden broom sticks painted black were positioned to stick out through the Plexiglass tail cap to deter enemy fighters attacking the rear. Thus modified, takeoff weight was 31,000 pounds, the maximum allowable for the B-25. Additionally, each aircraft’s engine carburetors were individually modified for lean operation in order to extend range.

B-25 under guard during the transcontinental flight

On March 25, 22 B-25s flew to McClellan Field in Sacramento, California, flying across the continent at 500 feet the entire distance to allow the crews to practice low level navigation. At McClellan, the crews discovered as they prepared to leave that the base mechanics, unaware of the mission, had re-set the carburetors for standard operation. Ted Lawson later remembered it took everything he could muster to not punch the Master Sergeant who told him, “I don’t know what those mechanics you’ve been working with think about this airplane, but they’ve put you in real trouble.” There was no time to fix the damage. They departed McClellan for Alameda Naval Base, where they first saw Hornet. The carrier and her escorts steamed under the Golden Gate Bridge headed west at dawn on April 2, 1942 and disappeared into a foggy Pacific Ocean.

B-25s aboard Hornet

John Bridgers recalled the voyage westward. “The Enterprise was along to provide scouting, anti-submarine and air defense for the force. My days were marked by tedium. The flight deck was kept ready with a coterie of planes, prepared for a deck-load launch at any time. Aircraft were launched repeatedly throughout the day with search and patrol flights kept airborne from sun up to sun down; one flight was launched and then the one in the air brought aboard every four hours. This necessitated taxying all the unused planes forward to clear the landing area. When the pilots manned their plane for this 15-minute exercise, they had to go with up-to-date navigational material, prepared to immediately launch rather than taxi if enemy contact occurred during this brief but critical time. LCDR Max Leslie was the skipper of Bombing Three and I was his ‘taxi’ pilot. I sat in the Ready Room most of the day, reworking my chart board every four hours or so and then taxied the skipper's plane forward. I was not allowed to fly on any of the patrol missions because I had not yet been carrier qualified in the SBD and Admiral Halsey, the task force commander, said he could not risk a plane for this purpose before our mission was complete. I wasn't unhappy that I had been brought along, but I couldn't exactly figure why that was. “

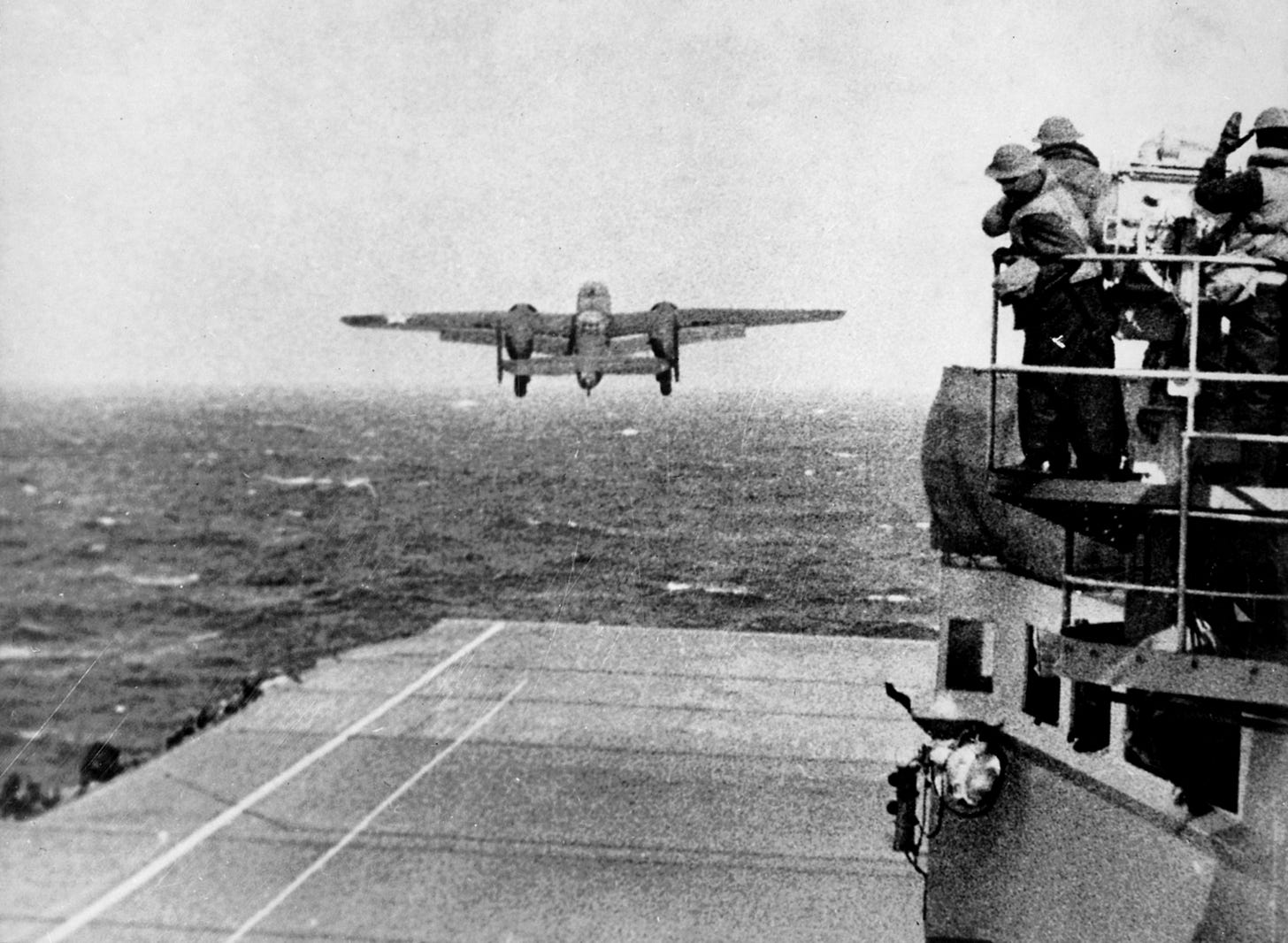

Mitscher watches Doolittle take off

The original plan called for the B-25s to be launched at dusk when the fleet was 400 miles from Japan, so that they would attack at night, flying on to land in China in daylight. However, at 0738 hours on April 18, 750 miles from Japan, a Japanese picket boat was spotted; before it was sunk radiomen aboard Enterprise detected that it sent a warning. Doolittle and Hornet’s Captain Marc Mitscher decided to launch immediately, 10 hours early and 200 miles farther east from Japan than planned. Even knowing they were unlikely to make it to China in this situation, members of the back-up crews who attempted to buy their way aboard the attackers were unsuccessful.

Doolittle takes off

John Bridgers remembered, “We watched the launch. It was hairy business for all of them, most of all for Colonel Doolittle who went first. They seemed unprepared to cope with the rough weather. In a fully-loaded condition and with the wind across the deck standardized to twenty-or-so knots largely obtained from the ship's headway this was no trouble. However, when the seas were high and the wind was strong, as it was now, extra air speed was easily attained in the deck run. All of them rushed into the air, having pulled up early. Fortunately none were hit by the rising bow. It was some time before they were all airborne and on their way, each plane alone as it disappeared into the murky skies. After the launch, the fleet immediately turned back east towards friendly waters while Doolittle's brave band flew west to only God knew what.”

By 0919 hours, the 16 bombers were flying west toward Japan.

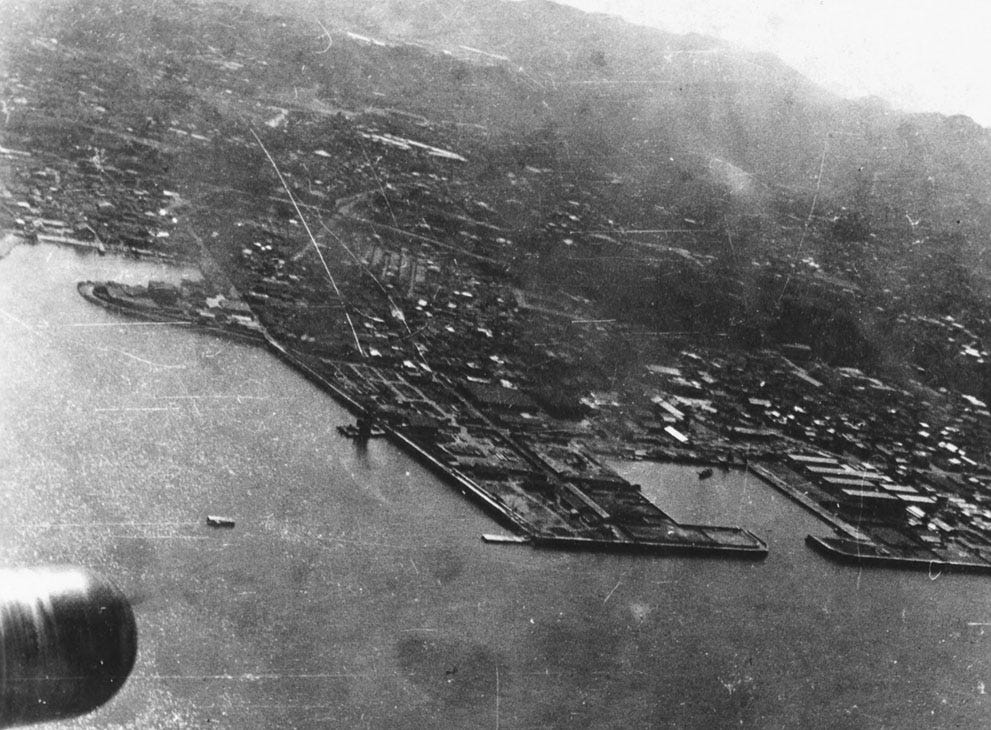

Over Yokosuka Naval Base in Tokyo Bay

The raiders arrived over Japan around noon. Their targets in Kobe, Yokohama, Nagoya, and Tokyo were successfully bombed and no planes were lost. However, bad weather in eastern China prevented the fliers finding their landing fields that night, since the Chinese had not received word of their arrival. The bases maintained radio silence, expecting a Japanese attack. Eleven crews baled out over the dark countryside while four others crash-landed, with seven crewmen injured and three killed. The crew of one bomber (40-2242) flew to Vladivostok because they were very low on fuel; the Soviets interned both aircraft and crew.

Lt. Robert Hite taken prisoner

Eight raiders were captured by the Japanese and tortured to reveal where they had come from; none ever revealed the facts of the mission, with four dying under torture.

Japanese examine wreckage

The Japanese response to the raiders having been sheltered and assisted by the Chinese was an orgy of death and destruction as the Imperial Army initiated “Operation Sei-go” to punish the Chinese for helping the raiders. Chinese peasants found with American equipment were shot immediately. Villagers were beheaded with samurai swords. Bodies were stuffed down village wells to poison them and fields were plowed up and salted. Germ warfare and other atrocities resulted in approximately 250,000 Chinese villagers being killed throughout eastern China over the next three months.

Doolittle believed the mission had been a complete failure and told his crew when they rejoined after parachuting from their plane in the darkness that he expected a court-martial on his return to the United States.

Doolittle’s wrecked bomber

Doolittle with Raiders in China

Such was not to be.

On his return, Doolittle was promoted to Brigadier General and awarded the Medal of Honor for his leadership. By the end of the year he became commander of the USAAF Twelfth Air Force in Tunisia and later commanded the Eighth Air Force in England, which he led to victory over the Luftwaffe that spring, as American bombers and fighters obtained the air superiority necessary for the invasion of Europe.

President Roosevelt made the official announcement about the raid, exercising his love of myth and mystery by stating that the planes had taken off from "Shangri-La," the mythical Himalayan kingdom that author James Hilton had immortalized in his novel, “Lost Horizon.”

Headline in America

The Tokyo Raid gave an incalculable boost to American home front morale when nearly every piece of news from the Pacific was of another defeat. The Japanese now knew their country was vulnerable to attack and they kept four first-line fighter groups in the Home Islands, despite losses incurred in the South Pacific.

More importantly, Admiral Yamamoto decided that an invasion and occupation of Midway Island to secure the western Pacific approaches to Japan would protect the Empire from further attack and lead to the crucial naval battle all members of the Imperial Navy knew was necessary to guarantee Japanese victory. June 4, 1942, was three days short of the six months he had promised when he said “I will run wild for the first six months; after that I can promise nothing.”

You can support That’s Another Fine Mess with a paid subscription for only $7/month or $70/year, saving $14. Your support with a paid subscription will be deeply appreciated now that my partner is gone and the financial situation here has changed.

Comments are for paid subscribers.

My father graduated from college in 1942 (with a rushed diploma) and joined the Army. He was assigned (recruited?) to the OSS. His first mission was to Vietnam to retrieve some Doolittle airmen. It was an incredible story; I’m sorry he never wrote about it. He only talked about it once with me and it was such a kaleidoscope that I can’t retrieve all the parts, except one:

He was with a radioman and, when they were attacked by Japanese troops, the radioman was lost so Dad was out of touch with the submarine. He had found the airmen but he couldn’t arrange for their pickup. The Japanese were losing territory to the Chinese and very soon the immediate area was under no one’s control. Dad went to the telegraph office and sent a wire to the American embassy, and he got a telegram back two days later saying where and when to meet the submarine.

A few corrections (I read Carroll Glines' histories of the raid and of the POWs from it as a boy, and somehow I remember a lot of it.). Ted Lawson is second from the left in the picture you posted, not the right. All eight captured Raiders captured were tried for war crimes in Japanese courts; three, 1LT Danny Farrow, 1LT Dean Hallmark (aircraft commanders) and a third, which I can't find the name of right now were executed. One other died in captivity, and four were liberated at war's end.

Another story, and I'm not sure if this was in Glines' history or where, was that GEN Arnold picked up LTC Doolittle in Washington DC. In the car, the General told Doolittle that they were going to the White House for FDR to award the Medal of Honor to him. As the story goes, Doolittle strongly objected, saying "I don't deserve the Big One!" and protested to the point where Hap Arnold basically gave him a direct order to accept the medal from Roosevelt. Doolittle went to his grave believing he did not deserve the Medal of Honor, but also lived the rest of his life to earn it.