Saturday night was spent away from today’s concerning news, as I watched a newly-restored classic movie about how fascism works.

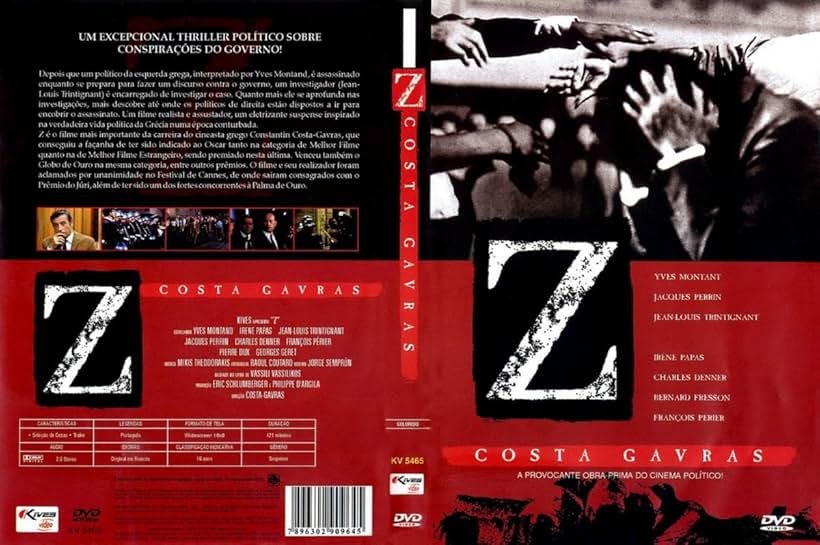

“Z” is a 1969 political thriller, the third film directed by Costa-Gavras, from a screenplay he co-wrote with Jorge Semprún, adapted from the 1966 novel “Z” by Vassilis Vassilikos. The film is the first fictional feature to be shot as though it was a documentary, which ups the immediacy of the pacing.

At the beginning, a title appears on-screen: “Any resemblance to actual people or events is not coincidental. It is intentional.”

“Z” is actually a recounting of the assassination on May 22, 1963 of Greek opposition leader Gregorios Lambrakis, who was fatally injured in a “traffic accident.” The accident theory smelled, and the government appointed an investigating magistrate, Christos Sartzetakis, to look into the affair. His duty was to reaffirm the official version of the death, but his investigation convinced him that Lambrakis had, indeed, been assassinated by a clandestine right-wing organization protected by high-ranking army and police officials who were implicated in the investigation. The plot was unmasked in court and sentences were handed down - stiff sentences to the little guys who carried out the murder, and acquittal for the influential officials who ordered it.

The title refers to a popular Greek protest slogan (Greek: Ζει, IPA: [ˈzi]) meaning "he lives," in reference to Lambrakis.

The film stars Jean-Louis Trintignant as The Examining Magistrate - based on Christos Sartzetakis, who became president of Greece 1985-90 when the opposition finally won the election they should have won in 1966; Yves Montand as The Deputy - Grigoris Lambrakis;

Irene Papas as the Deputy's wife Helene - Roula Lambrakis; Pierre Dux as The General - Konstantinos Mitsou; producer Jacques Perrin as The Photojournalist - a composite character, partly based on Giorgos Bertsos; Julien Guiomar as The Colonel who manages the plot- Efthimios Kamoutsis; Renato Salvatori as Yago, the driver of the assassination vehicle - Spyro Gotzamanis; and Maurice Baquet as The Mason, the man who identified the members of the fascist gang that carried out the assassination - Manolis Hatziapostolou.

Z was the first film - and one of only a few since - to be nominated by the Motion Picture Academy for both Best Picture and Best Foreign Language Film of 1970. It won the latter as well as the Oscar for Best Film Editing. It won the Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival by unanimous vote of the judges; the BAFTA Award for Best Film Music; and the Golden Globe Award for Best Foreign Film. At the time the film received this international recognition, Cost-Gavras was officially banned from Greece. The dictatorship was overthrown in 1974, following the Greek defeat in the Turkish-Greek war over Cyprus.

The film was shot in Algeria and centers on the right-wing, military-dominated government of an unnamed Mediterranean state based on Greece.

The story begins with the closing moments of a rather dull government lecture on agricultural policy until The General - the leader of the security police - takes over the podium and gives an impassioned speech describing the government's program to combat leftism by using the metaphors "a mildew of the mind", an infiltration of "isms" and "sunspots" in which he advocates changing the public school curriculum to inculcate “patriotism,” and a takeover of universities and the banning of unions to cement a “nationalist consciousness.”

The story then shifts to preparations for a political rally of the opposition faction in which the left-leaning, pacifist deputy (Lambrakis) is to give a speech advocating nuclear disarmament. There have been earlier attempts by the government to prevent the speech from being delivered, and the venue has been changed to a much smaller hall, as logistical problems have appeared out of nowhere; the people handing out leaflets about the change of venue are attacked by thugs under the command of the police.

On his way to the venue, The Deputy is hit on the head by one of the right-wing anti-communist protestors who are sponsored by the government, but carries on with his sharp speech. After giving his speech, The Deputy crosses the street from the hall, when a delivery truck speeds past and a man on the open truck bed strikes him down with a club.

The injury eventually proves fatal, and the police manipulate witnesses to force the conclusion that the deputy was simply run over by a drunk driver.

However, the police do not control the hospital, where the autopsy disproves their interpretation.

The Examining Magistrate, proddedby the revelations of The Photojournalist, proceeds to uncover sufficient evidence to indict not only the two right-wing militants who committed the murder but also four high-ranking military police officers. The action of the film concludes with one of the deputy's associates rushing to see his widow to give her the surprising news of the officers' indictments. The widow looks distressed and appears not to believe things will change for the better.

A telling moment comes when the General in charge of Internal Security - the man who gave the lecture about “weeding” in the opening scene - is asked by The Photojournalist if the case bears any similarity “To Dreyfus,” referring to the Dreyfus Incident that rocked Third Republic France at the turn of the 20th century. The General shrieks “Dreyfus was guilty!”

An epilogue tells the subsequent turns of events, which are directly from the Lambrakis assassination. Instead of justice being served, the prosecutor is mysteriously removed from the case, several key witnesses die under suspicious circumstances, the assassins receive relatively short sentences, the officers who planned and directed the plot receive only administrative reprimands, the assassinated deputy's close associates die or are imprisoned or deported, while the photojournalist who broke the story is sent to prison for disclosing official documents. The heads of the government resign after public disapproval, but before elections are carried out, a coup d'état occurs, and the military seize power in the coup that is known in Greek history as The Colonels’ Revolt of 1967. Modern art, popular music, avant-garde novelists, modern mathematics, classic and modern philosophers and the use of the letter "Ζ,"which is used by protesters against the former government, a reference to the assassinated deputy which means "He lives." (One of the authors banned by The Colonels was Mark Twain.)

“Z” was made in 1969 and appeared in the United States in 1970, the year following the FBI assassination on orders from J. Edgar Hoover of Black Panther leader Fred Hampton in Chicago with the collusion of Mayor Richard J. Daley and the active participation his son Richard M. Daley, then the States Attorney for Chicago and later the last Daley to be Mayor of Chicago in the 1990s. The evidence of the coverup of the Hampton assassination was finally coming to light in US media, and the parallels between Greek reality and American reality were obvious. Prints of the film were acquired by the Black Panther Party and shown at underground screenings.

Roger Ebert, who was not that well-known yet in 1970, named “Z” the best film of 1969, and wrote, "Z is a film of our time. It is about how even moral victories are corrupted. It will make you weep and will make you angry. It will tear your guts out.”

In 2009, Armond White praised the film and wrote: "Ending with a provocative, unorthodox tally of fascist clampdowns on freedom of expression and the arts, Costa-Gavras angles his exposé with a frightening coda that encapsulates the on-going political struggle. He avoids hippie optimism and foresees contemporary cynicism with a basic thriller device: a warning. Z carries the reverberations of that cultural shift from enlightenment to paranoia in each of its shrewdly devised tropes from common genres. Costa-Gavras expresses the tension and terror of political conspiracy that haunted the democratic and anti-war movement at the time.”

“Z” is listed on The 15 All Time Best Political Films. Paul Schrader, Paul Greengrass, Steven Soderbergh, Oliver Stone, William Friedkin and John Milius all list “Z” as influential on their work.

Having not seen the movie since I saw it at The Castro Theater in San Francisco 54 years ago, it was almost a “new” movie to me, watching it last night. It lives up to Ebert’s review. If you know the true story it is telling, it’s even better.

Now that it’s appeared on TCM’s regular programming, it’s available on-demand from TCM through Discovery Max.

It’s still A Movie For Our Times. Watch it.

Thanks to the paid subscribers who keep us going here. It’s only $7/month or $70/year.

Comments are for paid subscribers.

Yesterday I viewed a lively podcast with Marc Elias and George Conway,who has also donated 1 million to Harris campaign.Conway spoke of watching the German(subtitled) movie Downfall about Hitler’s last days in the Fuhrerbunker to try to grasp what it was like when his ex was working in Trump’s bunker.Regarding the future of the RNC, Conway pointed out that Trump had moved the RNC to Florida and merged it with his campaign…and what happens to political campaigns after a candidate loses ?

In the mean time, trying not to “drink the poison” and GOTV.💙🇺🇸

Z. I remember seeing it in an art house theatre in Memphis.

Paranoia is certainly rampant these days. Last night, I found myself sitting in a bustling, upscale Las Vegas restaurant with our two closest friends. It was my first outing since my beloved cat passed away last Sunday. I hadn’t wanted to go, fearing that I might break down in tears, especially knowing they would want to talk about him. Yet their invitation was so kind and sincere, we couldn’t bring ourselves to decline. And yes, we did talk about the loss of my sweet boy. But somehow, the conversation drifted into familiar territory—once again, the looming presidential election.

Our friends, who recently donated over $1 million to the Democratic National Committee for various campaign efforts, shared their thoughts. Think about that—over $1 million. They are, like us, a married lesbian couple. And, fraught with worry over the results of the coming election. I had the honor of officiating their wedding, and my wife was matron of honor for her best friend. We’re incredibly close, bound by years of shared memories, but last evening we found ourselves locked in a heated debate—whether or not, depending on the election, we should leave the country.

Tentative plans linger in the air. We have penciled in a trip to New York for Thanksgiving, and we’ve loosely mapped out a drive to Utah for Christmas. But “tentative” feels like the key word, a fragile placeholder in a world filled with uncertainty. How do you make plans when everything could go sideways? How do you sit across from three people who either believe the worst is inevitable or nothing will happen and we are overreacting? Aching with grief, I was too exhausted to think about it yet agreed we should have a plan.

We sat there, disagreeing in hard, jagged language, teetering between hope and dread. What do we do next? How do we carry on with our lives when everything feels so precarious? Do we start making evacuation plans like we did 37 times while living in Southern California? Or do we wait, paralyzed by the coming election, hoping for a clear answer afterward? Will we, like those in World War II, find ourselves scrambling for escape from a regime borne of Project 2025?

Paranoia. What an ugly word.