AMERICAN STALINGRAD - THE FINALE PART 3

ALL IN

The sacrifice by Admirals Callaghan, Scott and their men had only delayed the Japanese by a day.

Furious over Abe’s poor performance, Admiral Yamamoto immediately removed him from his command and directed Admiral Kondō to resume the mission. Kondō was described by other officers he had served with as an “English sort of officer, very gentlemanly, and good with his staff, but better suited for training command than battle.” He was well-respected by the “battleship faction” of the Imperial Navy, and was the senior admiral in the South Pacific.

Admiral Gunichi Mikawa’s cruiser force from the 8th fleet that had been originally assigned to cover the troop landing on November 13, was ordered to rendezvous with Kirishima and her escorts to finish the bombardment of Henderson Field. Mikawa’s fleet included the heavy cruisers Chōkai, Kinugasa, Maya, and Suzuya, the light cruisers Isuzu and Tenryū, and six destroyers.

Japanese cruiser “chokai”

That afternoon, after having turned back with Abe’s decision to withdraw, Admiral Tanaka’s 11 transports and their escorts turned to again head for Guadalcanal with plans to land the troops early in the morning of November 14.

The evening of November 13, with the remains of the U.S. fleet having withdrawn, Mikawa's force entered Ironbottom Sound uncontested. At 0155 hours on November 14, Suzuya and Maya bombarded Henderson for 35 minutes while the rest of the force stood off Savo Island to cover them if the Americans attempted to intervene.

Japanese battleship “Kirishima”

The bombardment caused some damage to aircraft and field facilities but Henderson was not put out of action. The Japanese withdrew toward Rabaul.

At 0712 hours that morning, Enterprise launched ten SBDs to search for Mikawa’s force. At 0915 hours, the carrier received a message came from Lt.(j.g.) Robert D. Gibson that he and Ens. R. M. Buchanan had spotted two battleships and two cruisers at 0850 hours. He had actually found Admiral Mikawa’s force, 230 miles north of Guadalcanal. After shadowing the force another 15 minutes, he broke out of the clouds and executed an attack on Kinugasa,. Dropping his 500-pound bomb on the cruiser from 1,000 feet at 0930 hours, his bomb hit forward of the cruiser’s bridge, killing the captain and executive officer. Kinugasa soon took on a 10-degree port list. Enterprise immediately put together a strike force and launched 17 SBDs at 0945 hours

Japanese cruiser “Maya”

Shortly after Gibson’s attack, Ensigns R.A. Hoogerwerf and P.M. Halloran showed up and pounced on Maya. Halloran held his dive too long and on pullout he clipped Maya‘s mainmast, crashing into her port side, igniting 4.7-inch shells from her secondary battery. The crash and explosions killed 37, but the cruiser was able to maintain position and speed with the others. At 1045 hours, 17 more dive bombers appeared over the fleet in response to Givson’s sighting report and initiated attacks. Heavy cruiser Chokai‘s boiler room was flooded by near misses, while light cruiser Isuzu’s steering was knocked out. Other near-misses knocked out Kinugasa‘s engines and jammed her rudder. At 1122 hours, Kinugasa capsized and sank, taking 511 of her crew with her.

Bombers from Enterprise and Guadalcanal also spotted and made repeated attacks throughout the afternoon on Tanaka’s transport force, sinking six transports and damaging a seventh so badly it was forced to turn back, later sinking. The four remaining transports continued on, stopping after nightfall to await the results of the second naval battle that developed that night.

Admiral Kondō, aboard the heavy cruiser Atago and accompanied by the heavy cruiser Takao, light cruisers Nagara and Sendai, with the destroyers Asagumo, Hatsuyuki, Shirayuki, Shikanami, Uranami and Teruzuki, rendezvoused with the Kirishima, Samidari and Inazuma the evening of November 13, but remained out of range of Henderson’s aircraft on the morning of November 14 while they refueled. The American submarine Trout (SS-202) spotted the ships and attempted to attack them unsuccessfully. Late in the afternoon, Kondō’s force headed toward Guadalcanal and came under an air attack that failed to stop them. The submarine Flying Fish (SS-229) spotted the fleet shortly after the air attack and managed to fire five torpedoes but failed to score. Her contact report informed Admiral Halsey that Guadalcanal was still under serious threat.

USS Washington (BB-56)

In the face of the threat, Halsey ordered the battleships Washington and South Dakota to leave Enterprise and proceed to the Solomons on November 13. This was a dangerous move on Halsey’s part because the two battleships and Enterprise were his last capital ships, and he was unable to give what was considered proper support, since there were only four destroyers available: Walke (DD-416), Benham (DD-397), Preston (DD-379 and Gwin (DD-433). None of the American ships had ever operated or trained together.

USS South Dakota (BB-57)

Task Force 54 was commanded by Rear Admiral Willis A. ‘Ching Chong’ Lee, considered the navy’s leading gunnery expert and known as a chain-smoking, approachable commander who relieved tension by reading lurid novels or swapping sea stories with the enlisted men standing watch duty on the bridge.

The next morning - November 14 - when the oncoming Japanese were spotted, the two battleships were 100 miles south of Guadalcanal. Halsey ordered them to proceed and enter Ironbottom Sound to stop the Japanese bombardment. Following an evening meal in which Lee briefed the ship’s officers on their mission and went over his expectations of how they would fight the battle, the force entered Ironbottom Sound and arrived off Savo Island at dusk.

Kondō’s force entered the sound shortly after 2200 hours. Shortly after, they were spotted and reported by PT boats from Tulagi. Kondō split his force, sending Sendai, Shikinami and Uranami to sweep the Savo’s east side while Ayanami swept the southwest side in search of Allied ships. The searchers spotted Lee’s ships at 2300 hours, though they misidentified the battleships as cruisers. Kondō ordered Sendai and her destroyers to join Nagara and her destroyers to engage the enemy before he brought Kirishima, Atago and Takao into position for the bombardment.

Washington’s radar spotted the Sendai force, but failed to detect the Nagara force. Washington and South Dakota opened fire on Sendai and her destroyers with radar control at 2317 hours. Lee ordered cease fire at 2322 hours when radar lost the ships. Sendai, Uranami, and Shikinami were undamaged.

The four American destroyers engaged Ayanami and the Nagara group. Walke and Preston were badly hit with gunfire and torpedoes. At 2336 hours, Preston‘s captain ordered “abandon ship” a minute before the destroyer rolled on her starboard side; her bow hung in the air for ten minutes before she sank, taking 117 men and her captain.

USS Gwin (DD-433) vs Japanese cruiser Nagara

At 2332 hours, Gwin was hit in her engine and put out of the battle. As Walke prepared to fire torpedoes, she was hit by a Type 93 torpedo at 2338 hours in the number two magazine; the explosion blew off her bow. Power and communication failed as the fires spread and her captain ordered “abandon ship” minutes later; when she sank, her depth charges exploded, killing 80 men in the water including Captain Fraser.

Benham’s bow was blown off by another torpedo; she withdrew before sinking the next day. The four destroyers had successfully screened the battleships despite their losses.

Most of the destroyer survivors drowned when Washington steamed through the wreckage of Walke and Preston as she opened fired with her secondary battery at Ayanami and set her on fire.

South Dakota suddenly suffered a series of electrical failures when her chief engineer locked down a circuit breaker in violation of safety procedures. The circuits repeatedly went into series, and her radar, radios, and almost all her gun batteries became inoperable.

South Dakota under fire

She followed Washington toward the western side of Savo Island until Washington changed course left to pass to the south behind the burning destroyers at 2355 hours. As she tried to follow, South Dakota was forced to turn starboard to avoid Benham, putting her between the fires and the enemy, thus silhouetting her.

South Dakota was forced to turn starboard to avoid Benham, leaving her silhouetted between the fires and the enemy.

Having received reports that the American destroyers had been destroyed, Admiral Kondō brought the bombardment force into Ironbottom Sound as he headed toward Guadalcanal in the belief the Americans had been defeated. Unknown to the admiral, his force and the two American battleships were now on a collision course.

Kirishima in combat November 14

Just before midnight, Kondō’ s ships sighted the silhouetted South Dakota and Kirishima opened fire on her while the destroyers also opened fire and launched torpedoes. Nearly blind and unable to effectively fire her guns, South Dakota managed a few hits on Kirishima while taking 26 hits that knocked out her communications and what was left of her fire control while fires broke out on her upper decks, forcing her to turn away at 0017 hours on November 15.

USS Washington in combat

As they concentrated their fire on South Dakota, the Japanese failed to detect the approach of Washington. At a range of 9,000 yards, Admiral Lee determined the target he was tracking was not South Dakota and opened fire on Kirishima at exactly midnight, hitting her with at least nine and possibly 20 16-inch shells and 17 5-inch hits from the secondary battery, most of which hit below the waterline. The hits disabled all of Kirishima's main battery, caused major flooding, and set her on fire while her rudder was jammed, forcing her to circle to port, out of control.

USS Washington opens fire

Kondō ordered all ships that were able to converge and destroy the enemy at 0025 hours, but the force could not locate Washington in the darkness since they had no radar.

Lee headed toward the Russell Islands to draw the enemy away from Guadalcanal and South Dakota. Kondō’s surviving ships spotted Washington at 0050 hours and the destroyers launched several torpedo attacks which Lee avoided as he withdrew from the battle. Believing the way was now clear for the transport convoy, Kondō ordered his fleet to break off at 0104 hours. By 0130 the Japanese had departed.

At 0155 hours, South Dakota managed to extinguish all her fires and a few minutes later she was back in communication with Washington. Lee ordered her to retire at her best speed.

Kirishima, badly battered, was still afloat. Like Hiei, her boilers and engines still worked, but the rudder was jammed 10 degrees starboard. Her commander, Captain Sanji Iwabuchi, fought to save his ship but the flooding was beyond control. He ordered the magazines flooded as fire spread through them but that only worsened the ship’s condition. Nagara rigged a tow. Kirishima limped behind, listing to starboard. At 0300 hours Captain Iwabuchi ordered the emperor’s portrait, transferred to Asagumo.

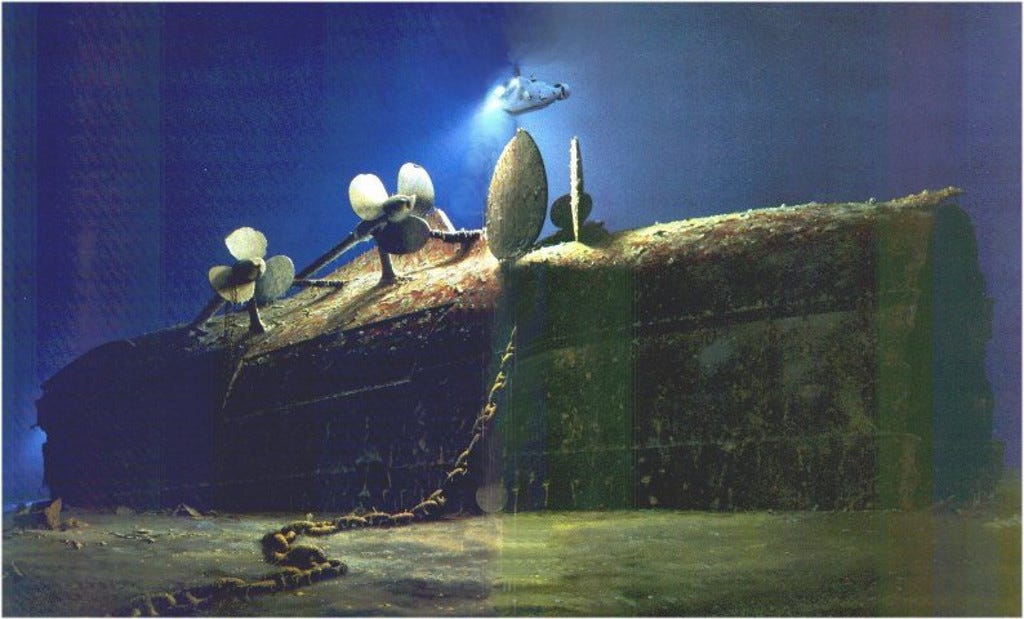

At 0325 hours, Kirishima rolled over and sank northwest of Savo Island. She was the second battleship the Imperial Navy had lost in two days and the first enemy battleship sunk by an American battleship since the Battle of Santiago Bay in the Spanish-American War.

Kirishima in Ironbottom Sound, discovered 1995

The badly-damaged Ayanami was scuttled by torpedoes from Uranami at 0200 hours, after which Uranami rescued Ayanami’s survivors. Kirishima’s survivors were rescued by Asagumo, Teruzuki, and Samidare. Kirishima was found in 1995 by Robert Ballard, upside down at a depth of 3,000 feet.

The four surviving transports beached themselves at Tassafaronga at 0400 hours. Admiral Tanaka’s destroyers unloaded their troops and raced back up the Slot to safer waters. Aircraft from Henderson spotted the beached transports at 0555 hours; they were battered by aircraft and Marine field artillery. USS Meade (DD-602) crossed from Tulagi and shelled them for nearly an hour, destroying all equipment that had yet to be unloaded and setting them afire, turning them into twisted wreckage wracked by internal explosions. Only some 2-3,000 troops of the 7,000 originally embarked made it ashore having lost most of their ammunition and food.

Beached Japanese transport

The Japanese failure to land the troops meant that there would not be another offensive mounted to take Henderson Field. From November 15 on, Admiral Tanaka’s Tokyo Express could only deliver ever-dwindling supplies by destroyer, dropping them in waterproof canisters to drift ashore.

Guadalcanal had been saved.

After the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, the U.S. Navy was able to regularly supply the island. Two fresh divisions of Army troops relieved the exhausted First Marine Division at the end of November and the surviving Marines were evacuated to Sydney, Australia.

The Imperial Navy would never replace its losses at Guadalcanal. Within a year, a new United States Navy would appear in the Pacific, stronger and better-organized than the fleet that fought at Guadalcanal, but it was the pre-war navy that held the line in the South Pacific in the darkest days of the war, making possible all that would come after.

The outcome of the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal was as strategically important as the victory at Midway. The significance was described by historian Eric Hammel: “On November 12, 1942, the Imperial Navy had the better ships and the better tactics. After November 15, 1942, its leaders lost heart and it lacked the strategic depth to face the burgeoning U.S. Navy and its vastly improving weapons and tactics. The Japanese never got better while, after November 1942, the U.S. Navy never stopped getting better.”

This final post of American Stalingrad: the Battle of Guadalcanal is open to all subscribers. You can access the entire series as a paid subscriber. There will be special posts for paid subscribers only.

Comments are open to all (until a troll arrives)

Thanks TC.

That you made sense out of that slug fest is mind boggling. Inspiring.