AMERICAN STALINGRAD: THE FINALE

This Veteran’s Day weekend marks the 81st anniversary of the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal over the next three days. This was the finale of the campaign, which saw victory emerge out of the darkest depths of the likelihood of defeat.

The story is inspirational, and I am making these final three posts available to everyone. We need some inspirational stories right now.

I note that this weekend, HBO2 (East) is showing the entire series “The Pacific,” starting tomorrow morning. Half of the series is devoted to the Battle of Guadalcanal, and they do a very good job of recreating the battle as experienced by the Marines on the island. The Guadalcanal section is based on “A Helmet For My Pillow,” Marine Robert Leckie’s superb first-hand account of the battle. The second half of the series is based on Marine Eugene Sledge’s great memoir “With The Old Breed: At Peleliu and Okinawa.”

Blog sez: catch it.

With that - the opening act:

GUADALCANAL: THE DARKNESS BEFORE DAWN

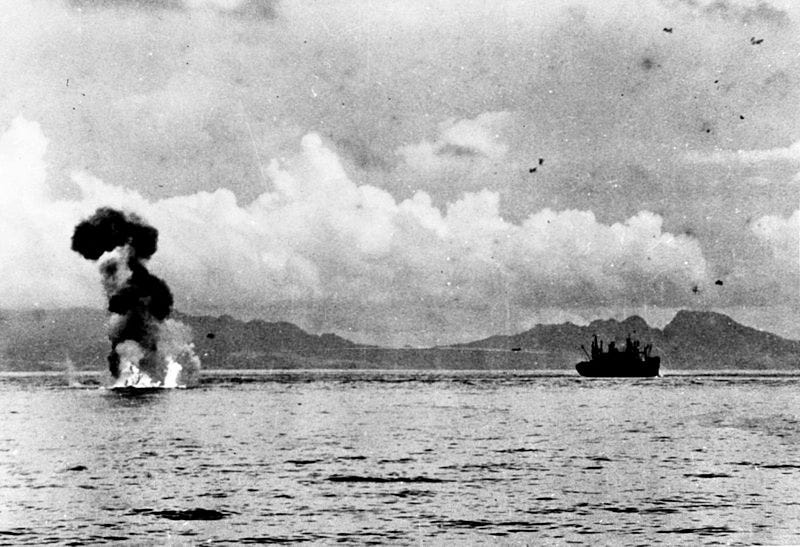

Two Japanese planes shot down attacking the convoy on November 11

Despite the defeat they had suffered in the October offensive to take Henderson Field, the Imperial Army remained committed to the goal of defeating the Marines and expelling them from Guadalcanal. Another attack was planned to take place in November. Before this could proceed, there was a need for further reinforcements. Eleven large transports were provided by Admiral Yamamoto to move the 38th Infantry Division’s 7,000 troops from Rabaul to Guadalcanal with ammunition, food, and heavy equipment. On November 9, Admiral Hiroake Abe’s battleships Hiei and Kirishima were ordered to deliver a second heavy bombardment of Henderson Field the night of November 12-13 to provide cover and allow the transports could unload safely in daylight the next day.

Among U.S. Naval commanders, there was doubt the Marines could hold Guadalcanal against the coming offensive. The Imperial Navy was known to be on the move. What was left of the U.S. Navy was badly outnumbered by their Imperial Navy opponents.

The “changing of the guard” at Henderson continued. Conditions and operation levels were such that a squadron was mostly used up in terms of losses, exhaustion of aircrews and wear and tear on aircraft over a tour of 4-5 weeks. Marine Air Group 11 had arrived at New Caledonia on October 30; on November 1, Major Joe Sailer’s 18 SBDs of VMSB-132 arrived at Henderson. The next day, an R4D delivered Major Paul Fontana and nine pilots of VMF-112. VMF-112, VMF-122, and VMSB-142 were all operational at Henderson by November 12 when they were finally joined by Lt. Colonel Paul Moret ‘s VMSB-131 TBF-1s, the first Marine unit to operate the Avenger.

Throughout the last week of October and the first week of November, Admiral Turner’s small scale resupply convoys continued to arrive at Guadalcanal. Running these convoys was difficult and dangerous, due to the constant threat posed by enemy ships and aircraft. Because of this, Turner’s convoys were limited in number of ships, because they were forced to arrive shortly after dawn and needed to be unloaded in order to depart before darkness. In early November, radio traffic analysis of the Imperial Navy and decoded Imperial Army radio messages revealed the enemy’s preparation of another round on Guadalcanal. Halsey demanded that Turner make an all-out resupply effort. On November 11, Task Force 67, the largest reinforcement and re-supply convoy sent to Guadalcanal since the invasion on August 7, arrived shortly after dawn. Two task groups commanded by Rear Admirals Daniel J. Callaghan and Norman Scott provided cover against an attack by the Imperial Navy, while aircraft from Henderson Field provided air cover.

In all, about 6,000 men were to be put ashore on Guadalcanal, including the Army 182nd Reinforced Regiment; Battery "L," Eleventh Marines, with their 155-mm. howitzers; the Army 245th Field Artillery Battalion; the 101st Medical Regiment; 1,300 officers and men of the Fourth Marine Replacement Battalion; Company "A," of the Army 57th Engineers; one quartermaster company; one ordnance company; and 372 naval personnel, as well as considerable ammunition. The ships coming from Espiritu Santo carried the First Marine Aviation Engineer Battalion, Marine replacements, ground personnel of Marine Air Wing One (MAW-1), aviation engineering and operating material, ammunition and food.

Unloading was delayed by two raids that day from Japanese aircraft based at Buin and it was soon obvious unloading could not be completed by dusk. Unloading continued through the night; many ships were empty by dawn, but more air attacks were expected, which meant it would be impossible to complete unloading before that night.

The task force maintained battle stations throughout the day of November 12 as waves of enemy planes attacked. Shortly after Turner’s transports arrived , Henderson was warned by Bougainville coastwatcher Paul Mason that 25 Bettys with eight Zero escorts were heading down The Slot.

At 0915 hours, VMF-121's Major Davis led Sam Folsom, Bob Simpson, Donald Owen, Joe Narr, Frank Presley, David Allen, Tom Mann, Roye Ruddell and Wallace Wethe, along with VMO-251's visiting CO Major William R. Campbell, VMF-212's 1st Lieutenant John Sigman and one of Paul Fontana’s VMF-112 pilots on his first mission, on a scramble to intercept a formation of Vals escorted by Zeros. In the fight, Loesch scored a Val while Allen and Presley each bagged a Zero; Sam Folsom claimed a Val for which he received credit for a “probable.” A Zero creased Davis’ cheek with a 20mm shell in burst that also hit his engine, but the 121 CO got back to Henderson safely. After Dave Allen got his Zero, the wingman got him; with his engine smoking, Allen pushed back the canopy and went over the side, to be picked up off Lunga Point. Unfortunately, Bob Simpson, Joe Narr and Roy Ruddell fell victim to either the enemy or the task force flak, and were listed as Missing In Action when they failed to return.

Tom Mann later described the events of November 11 in a letter to his wife:

“I spotted a flight of 12 dive bombers at 12,000 feet, starting their run on the ships. Approximately half of them had started their dives by the time I got in position. The remaining six or seven started their dives when I started shooting. I opened fire on the last one in a diving tail position. It smoked, then flamed and fell off. I then shot down the leader of that echelon, then picked up a third in its dive. I opened fire and it smoked and streamed fire. The bomb dropped as I fired, but I stuck with it and closed to about 300 feet. The bomb landed just to the north of a destroyer, and the bomber hit beside the explosion. I don’t remember the ship’s AA, but they had to be firing like blazes!

“As I pulled out of my dive, I saw another one heading north after it pulled out of its dive. I closed on his tail. The pilot fish-tailed as he tried to give his gunner a shot at me. I fired a short burst and it exploded in mid-air. I then noticed another one and went after it. Our speeds were pretty close and it took a long time to close on him. As I closed in I noticed he was really hugging the deck, so low his propwash was leaving a wake in the water. I opened fire and then I noticed another bomber to my left. The first one went down and I turned toward the one beside me, but his gunner opened fire. I got hit in the oil cooler under the left wing and in the cockpit and got shrapnel in my left arm and leg. My throttle got hit and was useless. I headed south toward home, but my engine quit midway between Savo and Tulagi and I made a dead-stick landing in the ocean. It must have knocked me out, because I came to and there was water in the cockpit. I hit the gunsight and broke some teeth. I got out but couldn’t inflate my boat. I inflated my Mae West and started swimming toward Tulagi. I was swimming from around 0930 to dusk.

“I landed on an island north of Tulagi and two natives found me and took me to a larger island, where I stayed for seven days while they treated my wounds. On November 18, I was returned to our base at Tulagi in a large dugout canoe rowed by 22 islanders. The entire trip was approximately 45 miles and was made in eight hours without a stop. The islanders chanted or sang religious songs for the entire trip. I returned wearing a Japanese dungaree uniform that the islanders gave me in exchange for my flight suit. They told me that the uniform was from one of three Japanese they had killed on their island. The doctors at the base removed six or eight pieces of shrapnel, up to an inch in size, from my left hand, left arm, and left leg.”

Mann later received the Navy Cross for his efforts with 121 and for shooting down a total of nine enemy aircraft, but November 11 was both the high point and the worst day of his tour.

At 1030 hours, Joe Foss and his “Flying Circus” managed to get to 29,000 feet in time to intercept the enemy, except they failed to show up. The incoming raid was lost by Cactus radar when it was near the eastern tip of Florida Island. This was because the bombers dived to execute a torpedo attack on the transports.

Foss spotted the Bettys low over Ironbottom Sound through a break in the clouds. The Flying Circus executed a wild dive to catch them. As the Wildcats dived into the warmer air at lower altitude, frost glazed their canopies. The wild dive created such terrific pressure that the plexiglass of Foss’ canopy was blown out and the walk strips were peeled off the Wildcat’s wings. Just as the Bettys began their attack run, Foss dropped into position 100 yards behind the trailing Betty. Opening fire, he set its right engine afire and it careened into the water below. Foss lined up a second Betty but was interrupted by a Zero; he turned on the fighter and exploded it just above the water. With these two victories, he had beaten John Smith’s score and was the leading American ace, with 21 shot down.

Unfortunately, NAP Master Technical Sergeant Joe Palko, who had taken off with Foss, was shot down and killed. His Wildcat crashed on Tulagi; when would-be rescuers got to the plane, he was found in the cockpit shot through the throat. Palko had been almost a father figure to the young pilots when they were first assigned to the squadron.

Major Paul Fontana led VMF-112 on their first interception. In a wild fight low over the waters of the sound, he shot four of the bombers into the water before they could drop their deadly torpedoes. The P-39 Airacobras of the 67th squadron also hit the attackers before they could drop, splashing the big green bombers into the water below.

Both Admiral Callaghan’s flagship San Francisco and destroyer Buchanan were hit, killing 30 and wounding 50. When a Betty was hit on its torpedo run by San Francisco’s gunners, setting it afire, the pilot deliberately crashed into her after machine gun platform,starting a fire. Boatswain’s Mate 1st Class Reinhardt Keppler led the firefighting while also supervising treatment of the wounded and removal of the dead, saving several lives.

USS San Francisco under attack by the Betty bombers

In the wild fight over the transports, the Marines claimed 17 Betty torpedo bombers and five Zeros for the loss of three Wildcats and an Airacobra. The transports continued unloading.

On November 12, the Japanese sent three raids over the course of the day. VMF-121 claimed two Zeros and ten Bettys in two interception missions. Shipboard AA claimed another ten.

Late in the afternoon of November 12, ComSoPac radioed a warning that a large enemy force had been spotted headed down The Slot. These were the ships Allied intelligence had been tracking. At the same time they came through Indispensable Strait into The Slot, Admiral Tanaka’s Tokyo Express transport force carrying the troops and equipment of the 38th Infantry Division departed the Shortlands. It was estimated the enemy would arrive at Guadalcanal shortly after midnight.

Admiral Turner ordered the two cover forces commanded by Admirals Callaghan and Scott combined into Task Group 67.4 with Callaghan in overall command. This unfortunate decision was made despite the fact Scott was the victor at Cape Esperance and had the experience to command in a night battle because Callaghan was senior in rank by two days; he had never held a combat command, having been Chief of Staff to Admiral Ghormley.

The orders were to stop the Japanese at all costs.

You can gain access to the entire American Stalingrad post, based on my books “Under The Southern Cross” and “The Cactus Air Force” by becoming a paid subscriber. There will other exclusive posts for paid subscribers coming soon.

Comments this weekend are for everyone.

I took the liberty of reposting the final episodes in this series since the landlord has unlocked the door. The timing is perfect. The bravery and patriotism of every man mentioned in these stories should embarrass the shit out of the chorus of cowards turning their backs on their duties in the House of Representatives. It won't because they don't care; but I do and my friends who will read this do also. It's Veteran's Day.

You said we need some inspirational stories right now and these deliver. Reading about our naval heroes is a great way to raise our fighting spirits as we face the Republican terrorists in their campaign to destroy democracy. I'm with C Towers and others on this one. The emphasis in the oath I swore back during the Vietnam war is now on the domestic enemies we must defeat no matter what.