AMERICAN STALINGRAD - PREPARATION

F4F-3 Wildcat in flight over San Diego, February 1942

In the aftermath of Midway, the Navy reorganized for the coming battles. One of the young pilots involved in all this was Ensign Francis Roland Register, who had immediately picked up the nickname “Cash” during his flight training at Pensacola. Register graduated with his Wings of Gold on December 12, the Friday after Pearl Harbor. While other aviators lamented in later years that they had followed the Navy-wide order not to keep a diary, Register was one of those few who defied the order and kept a concise account of his life in the Navy during the momentous year of 1942. Thus, he would give voice to the voiceless, the young fliers on the “sharp end of the spear” over the six weeks he would spend on the island in its darkest days before being evacuated for exhaustion.

Ensign Register arrived in Hawaii in January 1942, having taken the opportunity during his graduation leave to get married. When VF-3 returned with Lexington in mid-March, Register was assigned as wingman for Lt(jg) Marion W. Dufilho in the division led by Lieutenant Edward H. “Butch” O’Hare, now the first Navy ace of the war after his epic defense of Lexington against attacking Japanese bombers on February 17. Register later assigned all the credit for his survival at Guadalcanal to the on-the-job training he received from O’Hare and Dufilho.

Butch O’Hare in flight

Throughout the months after Pearl Harbor, Marine Aviators in Hawaii were standing up new squadrons. Lt. Colonel Richard H. Mangrum, who had learned the art of dive bombing flying in Honduras as a young Marine aviator back in 1928, had suffered the loss of all his squadron’s SB2U-3 Vindicator dive bombers during the Pearl Harbor attack. He later recalled to historian Eric Hammel that, over the spring of 1942, “We were reforming, joining new pilots, splitting squadrons like amoebas, with each half becoming a new squadron. Gradually, very gradually, new aircraft were made available.” The effort moved into high gear following the Battle of Midway as it became clear Marine fliers would soon enter combat in the South Pacific.

SBD-3 Dauntlesses over the Pacific

Two weeks after Midway, Dick Mangrum thanked the gods for having Captain Bruce Prosser report aboard from having flown SB2U-3 Vindicators in the battle, later describing Prosser as “the backbone of the squadron” while they trained, beloved by the younger pilots for his willingness to impart to them everything he had learned the hard way.

Around the same time Mangrum welcomed Bruce Prosser to his squadron, Marine Air Group-23's two fighter squadrons - VMF-223, commanded by Captain John L. Smith, and VMF-224, commanded by Captain Robert Galer - returned to MCAS Ewa from Kauai where they had flown as the sole air defense of northern Hawaii since early January. On arrival, the two were congratulated on their promotions to Major and informed they had six weeks to train the large group of newly-graduated 2nd Lieutenants waiting for them, before they would deploy to the South Pacific. In place of the F2A-3s that had demonstrated their combat inadequacy over Midway, there were brand new Grumman F4F-4 Wildcats on the flight line, to be divided between the two squadrons.

Major John L. Smith, CO VMF-223

Major Robert H. Galer, CA VMF-224

Years later, Galer - by then legendary as one of three Marine aviators awarded the Medal of Honor for combat at Guadalcanal, the place where they were then unknowingly headed - recalled that of his wartime accomplishments, “I was most proud of the fact that, with three other experienced pilots, I took 22 kids right out of flight school, and with 40 hours of training, qualified them to operate off an aircraft carrier, to fly their planes in combat, and use their guns effectively - tasks that before the war would have taken 40 hours of training for each. And every one of them acquitted themselves admirably when we got to Guadalcanal.”

The young pilots Galer trained - on Guadalcanal

John L. Smith, born December 26, 1914, in Lexington, Oklahoma, graduated from the University of Oklahoma in May 1936 with an ROTC commission as a 2nd lieutenant in the Army Field Artillery; he took a Marine commission that July. Entering flight training at Pensacola in July 1938, he pinned on the Wings of Gold of a Naval Aviator in July 1939 with an assignment to dive bombers. Over the following three years, he made a reputation for himself in the Corps as a tough, abrasive officer, a moody and sarcastic hard-driving disciplinarian, yet at the same time ambitious and determined. He was lucky to find three survivors of VMF-221 assigned to his unit. Marion Carl, Clayton Canfield and Roy Corry had flown together at Midway, calling themselves “the three Cs.” Carl became Operations Officer while Canfield and Corry became Third and Fourth Division Leaders respectively. The 22 young pilots they were now responsible for had an average of 180 flying hours in their logbooks and no time in Wildcats. Fortunately, gunnery was a fetish with Smith, who honed the squadron over the next five weeks; under his leadership, the pilots concentrated their efforts on improving their fighting and flying skills.

John L. Smith, Robert H. Galer and Marion Carl on Guadalcanal on being awarded the Navy Cross

On July 5, VMF-223's Smith and VMSB-232's Mangrum were informed they would be going to war in 30 days, departing Hawaii by the end of the month for the South Pacific to support the Marine landing in the Solomons.

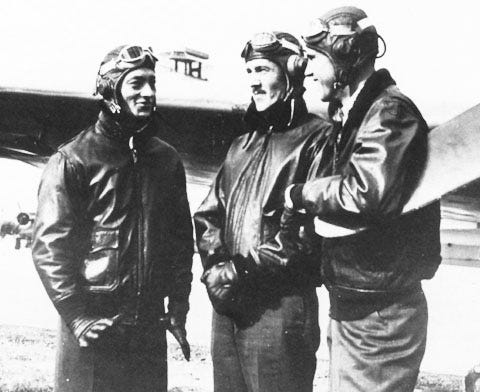

L to R: John L. Smith, Richard H. Mangrum, Marion Carl

Mangrum later recalled, “I was reasonably dumbfounded because my squadron within the month had been divided again. Some 12 new pilots who were fresh out of flight training in Pensacola had joined at the first of the month. Looking at their flight log books, I was appalled to discover that none of them had much over 200 hours in the air and that two of then had slightly less than 200 hours of flying of all types in the air, and none in the aircraft which we were equipped. I shall never forget being, of course, admonished that this was of the utmost top secrecy and that no one, NO ONE!, even my executive officer or anyone else in my squadron, was to be told where we were going. We were to be ready for combat, ready for departure on August 1st. So, I left the colonel's office and went back to my squadron's headquarters where I was greeted by my sergeant major, and his first question was, ‘Major, where's Guadalcanal?’ We had one solid month of working as hard as we could, day and night, to try to bring these people up to some degree of combat effectiveness.”

Following Midway, Ensign John Bridgers, who had survived the sinking of Yorktown, would receive a new set of size 14AA shoes to replace those he lost in the water, and went aboard Enterprise in July. Bridgers had arrived at Pearl Harbor in January, and later wrote that what he saw of the harbor a month after the attack revealed that “the results had been far more grievous than the country had been told.” Like nearly every American who would pass through Pearl Harbor before the last of the wreckage was removed in 1944, he swore an oath of personal vengeance against Japan. By now he had been a witness to the Doolittle Raid in April and a participant - albeit not an active combatant - at Midway. He later wrote that his experience of battle on Enterprise and at Guadalcanal as a member of “Flight 300" was the most intense period of his life.

On July 9, Air Group 5, previously the sunken Yorktown’s air group, went aboard Enterprise. Lieutenant Turner Caldwell - John Bridger’s commander - had taken command of Scouting Squadron 5 (VS-5) at the end of June. Three years earlier, fresh out of Pensacola after winning his Wings of Gold, Turner had reported to the squadron as Assistant Navigation Officer. He later recalled, “A week after we reported aboard, we learned the ship was headed for the South Pacific, with rumors flying everywhere through Enterprise that we would be involved in a ‘big operation.’ As it turned out, the rumors had no idea how big an operation we were about to become involved in.”

On August 1, “American Stalingrad” will go behind the TAFM paywall, where articles will be posted telling the story of the Battle of Guadalcanal through December. I hope you find the public articles posted on this story interesting enough to become a paid subscriber to get the rest of the story and support the work of this project. It’s only $7/month or $70/year.

Comments are for paid subscribers.

It's impressive how these flyers seem to be all in on the war--something that hasn't happened since WWII as far as I know. This is stuff I never would have looked for on my own, and I'm happy to be reading it. I love the photos too!

During WWII my father was a radar mechanic at the far end of the shuttle bombing, dubbed Operation Frantic, in which allied bombers left England to bomb Germany and German-held territory. But instead of having to fly all the way back to England, they could fly the relatively short distance to Poltava or Mirgorod, and land in one of the three US bases in what was then USSR and is now Ukraine. He was there from May 1944 to--if I remember correctly--late summer 1945, and learned Russian well enough to become one of the foremost experts on the Soviet economy.

Brooklyn born and raised, he finally learned to drive on one of the bases in Ukraine, in a Jeep. The story is well told in Forgotten Bastards of the Eastern Front: American Airmen Behind the Soviet Lines and the Collapse of the Grand Alliance, by Serhii Plokhy, a Ukrainian scholar at Harvard, who took advantage, among other things, of a KGB file on my father that we only found out existed in 2017, from which we learned--among much else--that a Russian woman he'd gone out with there, who disappeared on him, had been told by the Soviet authorities she must ditch him.

And I finally learned a bit about what he'd been doing on his first postwar return trip to Russia, which took place when I was about to turn 5, while he was gone for six weeks. I didn't understand how the mail worked, but one day during that period I'd colored something on some construction paper. I'd taken my childish creation outside and lofted it, hoping the winds of Cambridge would somehow convey it to him in the mysterious land over the mysterious sea. And there, in the prologue of Plokhy's book was a vignette about my father being followed and questioned by a couple of incompetent KGB officers during that very period. Yes, all these years later, it was a (minor) relief to have an account.

Beautiful work, TC. Thats Another Fine Mess is the greatest subscription value on Substack. BTW, thanks for the Thom Hartmann recommendation--another great value in journalism with integrity.